Differential radiological semiotics of coronavirus infection and other etiology pneumonias

REVIEW

Differential radiological semiotics of coronavirus infection and other etiology pneumonias

Article Summary

- DOI: 10.24969/hvt.2021.251

- Page(s): 66-74

- Education

- Published: 07/05/2021

- Received: 30/04/2021

- Revised: 06/05/2021

- Accepted: 07/05/2021

- Views: 8489

- Downloads: 6439

- Keywords: COVID-19, chest CT - computed tomography, Imaging of chest, pneumonia, viral pneumonia, pulmonary edema

Address for Correspondence: Aliya Kadyrova, I. K. Akhunbaev Kyrgyz State Medical Academy, 92A, Akhunbaev str., 720020, Bishkek, Kyrgyz Republic. Email: al_kadyrova@yandex.ru

1Radiology Department I. K. Akhunbaev Kyrgyz State Medical Academy,

2URFA Center of Radiology, Bishkek, Kyrgyz Republic

Abstract

In this review article we summarized the differential diagnosis of radiological signs of pneumonia associated with COVID-19 infection and emphasized learning points.

Key words: COVID-19, chest CT - computed tomography, Imaging of chest, pneumonia, viral pneumonia, pulmonary edema

Introduction

COVID-19 is a highly contagious disease that has spread worldwide. Disease management strategies are dependent primarily on early diagnosis (1). The gold standard for COVID-19 diagnostics is a reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction test (RT-PCR), but early testing by RT-PCR has yielded sub-optimal results, and it is known that patients with COVID-19 even with the use of reliable testing methods may initially have a negative result (2). So, in the first half of 2020, radiology, as an imaging modality, became the advanced method of pulmonary and other organs involvement diagnosis during the COVID-19 outbreak. Computer tomography (CT) and X-ray imaging were the most frequent and valuable studies of the thoracic organs, although radiography is not specific to COVID-19 and there are frequent discrepancies in both radiographic and clinical manifestations (1-3).

The Consensus Statement of Experts of the Radiological Society of North America on COVID-19 chest CT claims that in some cases changes in the lungs may even precede positive PCR result. CT is more sensitive than radiography in visualization of lung changes in COVID-19 disease; however, research analysis indicates that a minority of patients had CT findings before they were visible on radiography (2). Previously, high resolution CT was a screening method for the diagnosis of COVID-19 associated pneumonia, regardless of the severity of the disease in countries with poor epidemiological state. This was in relation to development of patient management algorithms: evaluation of clinical manifestations, laboratory, radiological data correlation and definition of therapeutic tactics (4).

At present, Radiological Society of North America does not recommend the use of CT as a screening tool (2). Currently, preference is given to categories of patients suspected of acute respiratory distress syndrome, in case of clinical deterioration in intensive care unit or for differential diagnosis with other pathologies in thoracic imaging. Such tactics are defined by experience, considerations of infection and radiation control policies and prevention of radiology department overload, especially in general hospital (5).

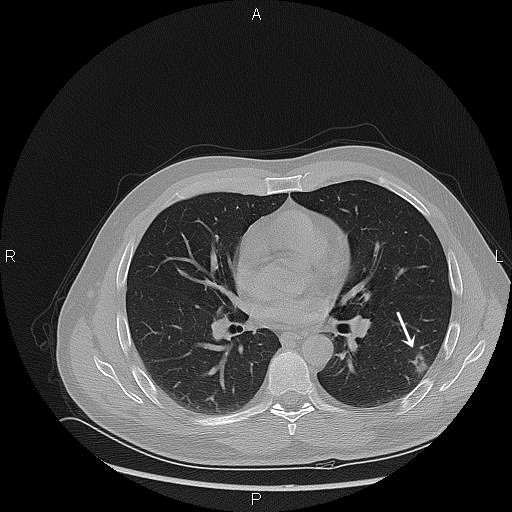

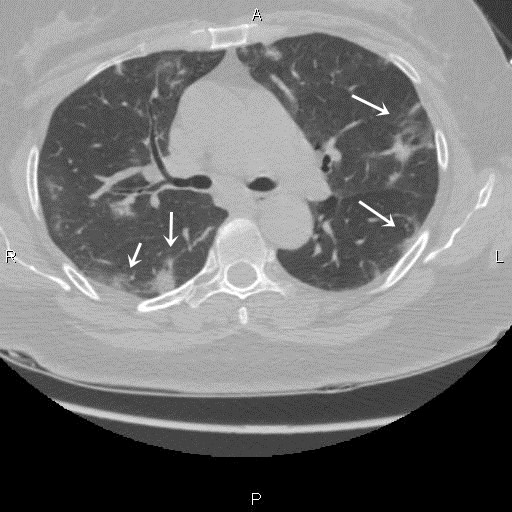

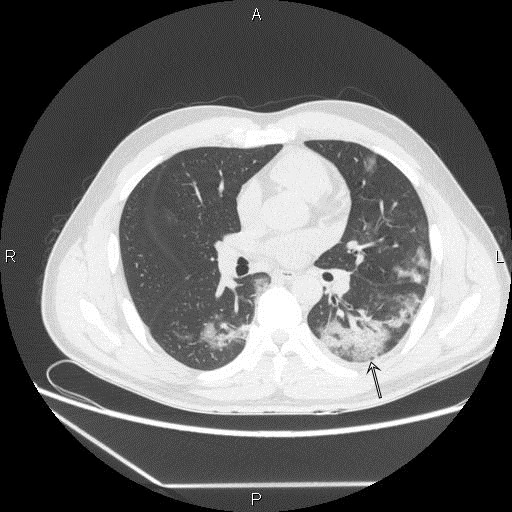

Identifying main radiological signs on CT are ground-glass opacity (GGO, Fig. 1) and air space consolidation. Lesions are most often bilateral; subpleural with peripheral or posterior spread, mainly in the lower zones (Fig. 2). Diffuse consolidation was also observed, but relatively rare.

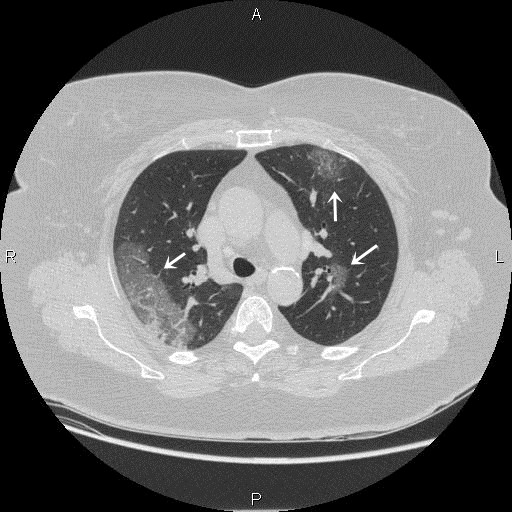

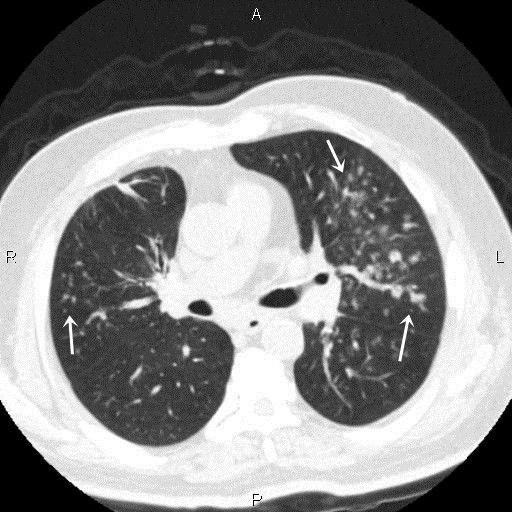

The results of radiographs described in patients with COVID-19 are similar to those who underwent CT and include: GGO, consolidation and hazy lung appearance (6) with basal and peripheral areas predominance (Fig. 3, 4-1, 4-2).

Although these results are common in patients with COVID-19 associated pneumonia, they are not specific and can be observed in other conditions such as other viral pneumonia, bacterial pneumonia, connective tissue diseases and idiopathic conditions.

The purpose of this article is to justify and demonstrate a differential diagnostic approach to the study, tactics and evaluation of radiological symptoms of coronavirus pneumonia with pathologies mimicking it.

Questions

1.Is CT-imaging able to determine the severity coronavirus pneumonia?

a. Yes

b. No

Correct Answer

A. Yes, and this is generally determined by the number of GGO foci: if there are less than three foci with a diameter less than 3 cm, this can be considered as mild course; if there are more than three foci up to 3 cm in diameter, or a combination with consolidation sites is the moderate/ severe course. Diffuse ground-glass opacity or crazy paving sign can be considered as severe course.

Also, in diagnostics of COVID-19 radiologists use visual evaluation of severity of lung damage, where each of the five lung lobes is valued on a scale of five: if there is no pathology, “0” points will be assigned; minimum lung injury equals 1 point (5% involved). Mild lung injury equals 2 points (5% - 25%), a moderate involvement equals 3 points (26% - 49%) and a severe involvement equals 4 points (50% - 75%) (7).

However, radiology alone cannot determine the course of a disease, and careful comparison with clinical information is necessary to clarify the severity of the disease.

2.Is it possible to differentiate coronavirus associated pneumonia from bacterial and atypical pneumonia on CT?

A. Yes, always

B. Does not always work (no, not always)

C. No, never

Correct Answer

B. Does not always work. Common features of the majority of viral pneumonias are: ground-glass opacity, patchy consolidation, inter-/intralobular septal thickening

Viral pneumonia

For example, despite the similarity of the element distribution - bilateral - as opposed to coronavirus pneumonia, influenza-induced pneumonia is not only manifested by GGO foci and patchy consolidation, but peribronchovascular thickening (bronchovascular bundles) and small-nodular opacities, pathogenetically related to necrotizing bronchitis and alveolitis (8). Mediastinal lymphadenopathy is not specific sign for coronavirus pneumonia, and may be present in other viral pneumonias (9). Fair point, that seasonality of the infection and contagiosity should be considered. For example, Herpes viruses have a tendency to develop pulmonary lesions in immunocompromised patients: those receiving radiotherapy or chemotherapy, HIV positive or elder patients; while seasonal infections - influenza, parainfluenza, adenovirus - can involve large populations. Therefore, the epidemiological situation has to be reflected in differential diagnosis of viral pneumonia and coronavirus, in particular. And it is yet unknown whether the coronavirus outbreaks will be as intense and repetitive or «seasonal», but we should never ignore other viral infections (10-12).

|

|

Figure 1. Small focus of the GGO in the left lower lobe. Third day of illness, fever 37.4°, cough. Laboratory confirmed COVID-19 pneumonia. GGO – ground-glass opacity

|

|

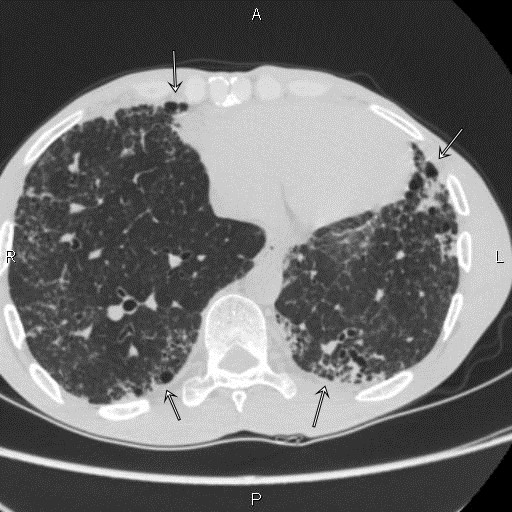

|

Figure 2. Multiple foci of ground-glass opacities in both lungs. Eighth day of illness, fever 38.4°, cough. Laboratory confirmed COVID-19 pneumonia. |

|

|

Figure 3.Typical subpleural area of GGO of right upper lobe and small foci of GGO in the left lung, dyspnea. Sixth day after symptoms onset. Cough, fever, pleuritic pain, nasal congestion. Laboratory confirmed COVID-19 pneumonia. GGO - ground-glass opacity |

|

|

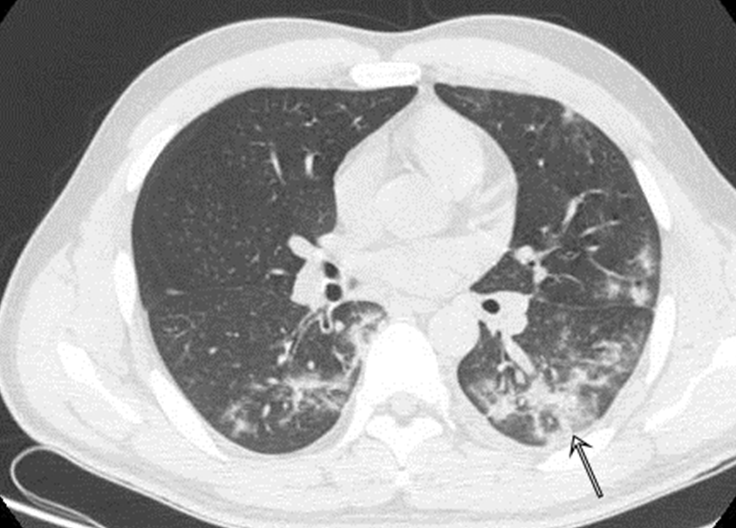

Figure 4-1. Bilateral subpleural GGO, fused into larger areas in the left lower lobe. Four days of illness, fever, dizziness. Laboratory confirmed COVID-19 pneumonia. GGO - ground-glass opacity |

|

|

Figure 4-2. The previous patient, CT scan five days later, no significant improvement. CT – computed tomography

|

Bacterial pneumonia

Diagnosis of bacterial pneumonia is also important, as any viral infection can be complicated by secondary infection. There are few pathophysiological changes: direct damage of alveolocytes, leading to gas diffusion violation and/or lung collapse formation; or bronchial epithelium damage, resulting in the disruption of the normal mucus passage; suppression of alveolar macrophages and depletion of the immune system; increased alveolar-capillary permeability, etc. All of the above creates a favorable environment for the overlaying of bacterial flora.

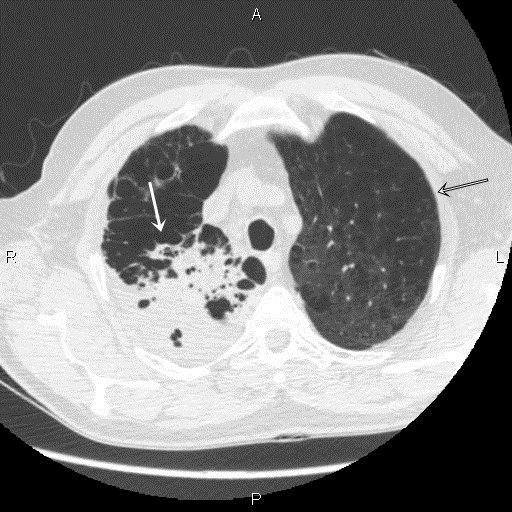

Radiologists and clinicians face an important task in recognizing «whether bacterial pneumonia has joined or not yet» on which further tactics will depend. In bacterial pneumonia (from the symptoms onset), consolidation is considered to be the prevailing symptom (Fig. 5).

Due to greater «compaction» of tissue by fluid, blood elements, debris and pus, GGO foci becomes more intense on chest X-Ray or CT. Other feature is distribution: anatomical (segmental, lobar) and basal. Thus, bacterial inflammation gives new symptoms - cavity formation, centrilobular nodules, «tree in bud» sign (Fig. 6), peribronchial thickening, pleural effusion and mediastinal lymphadenopathy (10, 11).

|

|

Figure 5. Multiple centrilobular foci: «tree in bud» sign, in the patient with bilateral bacterial bronchopneumonia, presented with fever, cough. COVID-19 PCR is negative. PCR – polymerase chain reaction test |

|

|

Figure 6. Fever, productive cough, dyspnea. Right upper right-lobe air space consolidation (white arrow). Bacterial pneumonia in patient with history of emphysema (black arrow). COVID-19 PCR negative. |

Fungal pneumonia

In a result of severe immunosuppression, fungal pneumonia can develop as an opportunistic infection. Some of the most frequent pathogens are aspergillus, mucormycosis and candidiasis, but other species (cryptococcosis, coccidiodomycosis) may also be observed. The diagnostic difficulty hides in round shape of GGO foci in aspergillosis, formed both in manifestation and resolution of coronavirus pneumonia. One of the pathognomonic processes – invasion and occlusion of vessels by hyphae leads to infarction and perifocal hemorrhage formation. This process resembles nodular consolidation with perifocal GGO – “halo sign” (Fig. 7). Another characteristic radiological finding is soft-tissue mass formation within pre-existed cavities (tuberculous caverns, bronchogenic cysts, etc.). This reflects in “air-crescent sign” (13). Other radiological signs include centrilobular nodules, pleural effusion, mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Since invasive diagnostic methods (biopsy) are not always possible, alertness of clinicians is required first of all in recognizing such pneumonic lesions, drawing their attention to the population and the probability of developing certain complications (10, 11).

|

|

Figure 7. Nodular opacity with perifocal ground-glass opacity, “halo sign”, of right upper lobe in a patient with cough. Invasive aspergillosis. |

3.Is the idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis characteristic to COVID-19?

A.Yes

B.No

Correct Answer

A. Yes, with the resolution of coronavirus pneumonia, pneumofibrosis may be formed and should be differentiated with a number of other fibrotic pulmonary pathologies - organizing pneumonia, interstitial lung disease, lung disease in systemic diseases, alveolar proteinosis, etc.

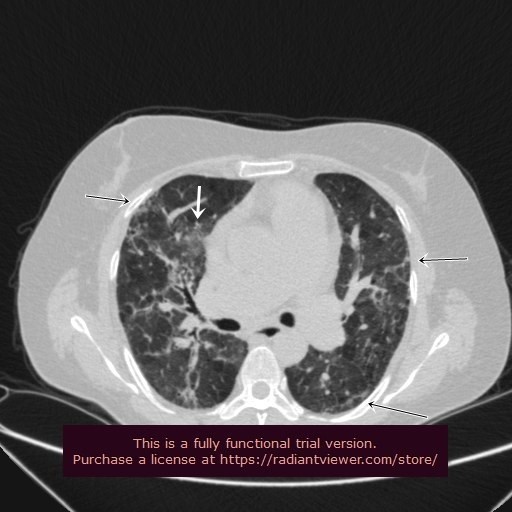

Leading radiological symptoms in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis are similar to COVID pneumonia, those are GGO, interlobular septal thickening with peripheral and lower zones predominance (Fig. 8-1 and 8-2). But unlike coronavirus pneumonia, isolated GGOs are almost never found, but are accompanied by peribronchial or septal thickening, honeycombing, traction bronchiectasis, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy (14).

|

|

Figure 8-1. PCR positive coronavirus pneumonia in resolution. Weakness, dyspnea. Pneumofibrosis (black arrows) with ground-glass opacity (white arrow). PCR – polymerase chain reaction |

|

|

Figure 8-2. Dyspnea and cough. COVID-19 PCR negative. Bilateral pneumosclerosis, with the formation of a honeycombing in subpleural zones (black arrows). History of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. PCR – polymerase chain reaction |

4. What is the basis for differential diagnosis of viral pneumonia from pulmonary edema?

A. Cardiomegaly, pleural effusion, crazy paving pattern

B. Gravitational fluid redistribution

C. GGO, cardiomegaly, Kerley lines, crazy paving pattern

Correct Answer

B. Gravitational fluid redistribution

Another frequent condition due to the prevalence of cardiovascular disorders or possible complication of COVID pneumonia is pulmonary edema. If pulmonary edema considered from the perspective of viral infection, then direct cardiotoxic or viral damage, hypoxemia due to respiratory damage can lead to cardiac failure. In case of pulmonary edema, regardless of etiology, patchy or diffuse GGO, interlobular thickening can be found, but undistinguishable from coronavirus pneumonia. However, pleural effusion, cardiomegaly and most importantly gravitational fluid redistribution are main differences between viral pneumonitis and edema (Fig. 9-1 and 9-2). Of course, the history of cardiac pathology, laboratory and echocardiographic data will help to clarify condition (15).

|

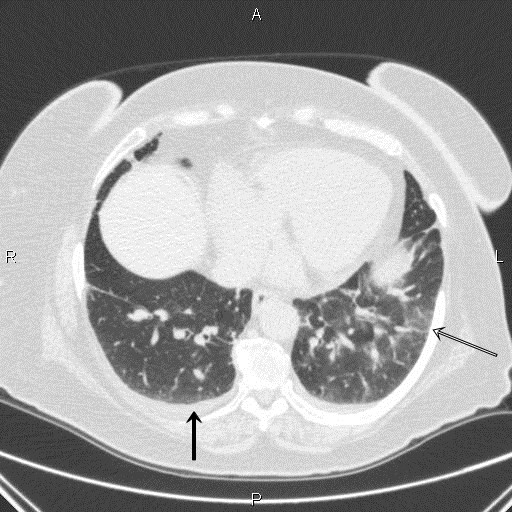

|

Figure 9-1. Bilateral ground round-glass opacity foci in supraphrenic areas (black-outlined arrow), interlobular septal thickening, bilateral pleural effusion (black arrow) in patient with severe dyspnea. COVID-19 PCR negative. Interstitial pulmonary edema. Supine position. PCR – polymerase chain reaction |

|

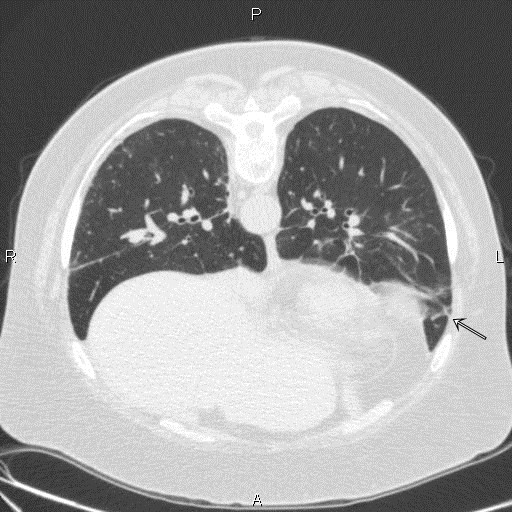

|

Figure 9-2. Same patient, prone position. Gravitational fluid redistribution – GGO foci in the left lung translocated anteriorly (arrow). GGO – ground-glass opacity, PCR – polymerase chain reaction |

5. Are pleural effusion, tree-in-buds sign and lymphadenopathy are typical in viral pneumonia?

A. Yes, always

B. More common with bacterial infection

C. No, not typical

Correct Answer

B. More common in bacterial infection

COVID-19 associated pneumonia can mimic other pulmonary infections, and presence of relatively non-typical results such as pleural effusion, lymphadenopathy, lobar consolidation or centrilobular nodular opacities. These radiological findings are much more common in bacterial pneumonia than in coronavirus pneumonia.

Conclusion

In conclusion, all above described patterns, though being widely known to the audience, are not always specific. In practice, it is not only difficult, but reckless to distinguish pathological conditions, using medical imaging alone as decisive. Consideration of steps such as: anamnestic data (post-transplant conditions, immunosuppression and radiation therapy), epidemiological situation (predominance of seasonal infections) and previous therapy should be valuable information in each case of coronavirus pneumonia on one hand, and alertness of clinicians and collegiality – on another, are paramount in providing necessary help to patients.

Peer-review: External and internal

Conflict of interest: None to declare

Authorship: A. K. - Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing, Review & Editing; I.A. - Resources, Data Handling; B.K. - Writing Original Draft; I.K.- Writing, Review; I.B., K.I., Ch. Zh. - Visualization, Software; A.A. - Methodology, Validation; all authors – Critical Review and Approval of a Final Draft.

Acknowledgments and funding: None to declare

References

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ketmen Ridge, Almaty region, Kazakhstan, August 2020. Dina Dyusupova, Aktobe, Kazakhstan.

Copyright

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

AUTHOR'S CORNER