Recovery of baseline renal function after treatment for prolonged in-stent artery thrombosis, in a COVID-19 positive patient: a case report

CASE REPORT

Recovery of baseline renal function after treatment for prolonged in-stent artery thrombosis, in a COVID-19 positive patient: a case report

Article Summary

- DOI: 10.24969/hvt.2023.382

- CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASES

- Published: 12/04/2023

- Received: 20/02/2023

- Revised: 08/04/2023

- Accepted: 08/04/2023

- Views: 5773

- Downloads: 4268

- Keywords: Chimney, ChEVAR, Renal, Stent, Covid-19, Neurovascular

Address for Correspondence*: Fabio Massimo Oddi, Policlinico Tor Vergata, Viale Oxford 81, 00133 Rome, RM, Italy. ORCID 0000-0001-8081-807X; E-mail: fabio.massimo89@gmail.com Phone : +39 0620902833.

Bernardo Orellana D., Viale Oxford 81, Policlinico Tor Vergata. 00133 Rome, RM, Italy

E-mail: bernardo.orellana.d@gmail.com Phone: +39 0620902834.

Fabio Massimo Oddi1*, Bernardo Orellana D. 2*, Mauro Fresilli 2, Daniele Morosetti 3, Arnaldo Ippoliti 2

1PhD course in Microbiology, Immunology, Infectious Diseases, and Transplants (MIMIT), University of Rome Tor Vergata, Rome, Italy

2Department of Surgery, Division of Vascular Surgery, University of Tor Vergata, Rome, Italy

3Department of Interventional Radiology Unit, University of Tor Vergata, Rome, Italy

Abstract

Objective: Acute renal in-stent thrombosis is common, especially after complex endovascular treatments, or in case of risk factors such as Covid-19 infection. Irreversible renal damage occurred when the renal artery was occluded for more than 3 hours. In this case, we present a case of renal function recovery after thromboaspiration of a renal stent thrombosis for more than 72 hours.

Case presentation: A 88-year-old man who tested positive for COVID-19 presented to the emergency room with dyspnea and anuria. He referred a previous complex endovascular intervention with the triple chimney technique (ChEVAR). More than 72 hours passed between the onset of symptoms to the diagnosis of acute renal intra-stent thrombosis. He underwent urgent thromboaspiration with neurovascular devices returning to his baseline renal function.

Conclusion: Despite the prolonged ischemia, renal revascularization with thromboaspiration restored renal function and rescued the remaining renal parenchyma.

Keyword: Chimney, ChEVAR, Renal, Stent, Covid-19, Neurovascular

Introduction

Complex endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) involves extension of the proximal aortic seal zone with preservation of branch vessel patency. Chimney graft-EVAR (ChEVAR) offers an alternative to combat hostile proximal neck anatomy, but uncertainties remain over target vessel's patency and type Ia endoleaks. In-stent acute renal thrombosis is a common scenario, especially after complex endovascular interventions with the chimney technique (1).

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection (COVID-19) is a disease characterized by an elevated risk of thrombosis and it increases the risk of local micro thromboembolism and all types of stent thrombosis (2-5).

The current literature suggests that irreversible renal damage can occur within 3 hours of renal artery occlusion (6).

This case report describes a treatment with mechanical aspiration thrombectomy in a COVID-19 positive patient presenting with acute renal chimney thrombosis after triple ChEVAR.

Case report

An 88-year-old male presented to the emergency room with epigastric and left lumbar pain, anuria, fever, and dyspnea, which had begun 24 hours before admission. Vital signs showed a body temperature of 38°C, blood pressure of 210/100 mmHg, heart rate of 110 bpm, respiratory rate of 25 bpm, and oxygen saturation of 92%; the lung auscultation revealed rhonchi and diminished pulmonary murmur and signs of cardiac overload. He had a history of hypertension treated with ramipril, previous smoker, ischemic cardiopathy treated with aspirin, and chronic renal disease stage III with just the left kidney functioning.

Five years prior to presentation, he underwent ChEVAR with triple chimney to the superior mesenteric artery and both renal arteries and abdominal aortic aneurysm. The thrombosis of right renal stent developed three years earlier, without an immediate diagnosis and treatment.

Laboratory tests yielded a potassium level of 5.0 mEq/L, D-Dimer - 3560 ng/mL, prothrombin time - 15 sec, C-reactive protein - 179.60 mg/L, serum creatinine of 2.16 mg/dl, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) - 195 U/L, with a baseline estimated glomerular filtration velocity of 13.6ml/min/1.70m2. After 9-hours, creatinine was 3.02 mg/dl and LDH 409 U/L and after 20 hours, the levels were 5.67 mg/d and 1141 U/L, respectively. The pattern continued until reaching a creatinine of 8 mg/dl after 36-hours.

On screening for COVID -19, the patient had a positive RT-PCR on nasopharyngeal swab testing. The patient was not vaccinated because the COVID vaccine was not yet available.

The patient underwent hemodialysis.

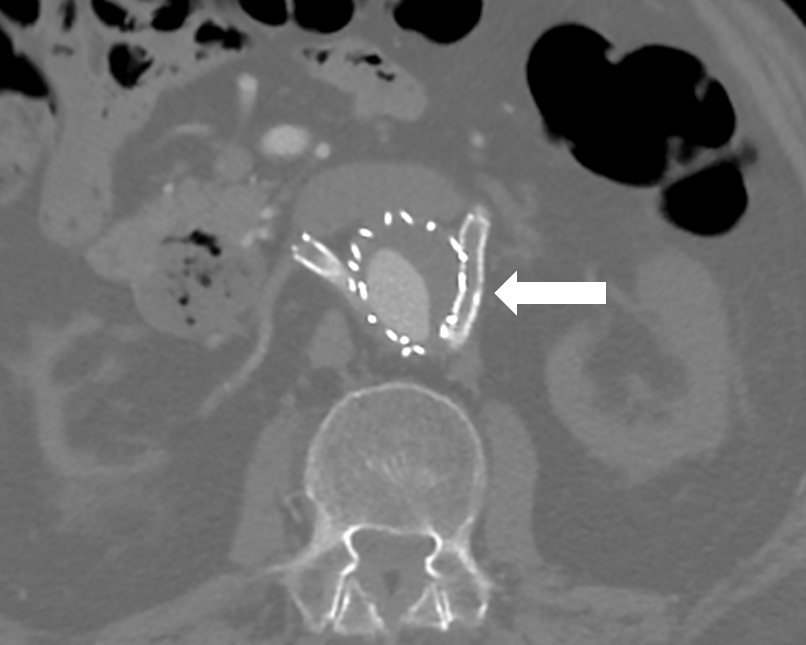

A chest radiograph showed no signs of pulmonary oedema. Doppler ultrasonography (USG) was negative for an obstructive urological disease and with a computed tomography angiography (CTA) he was diagnosed with acute thrombosis of the left renal stent with minimal distal contrast flow (Fig. 1)

After multidisciplinary evaluation, despite the prolonged time until the diagnosis, the patient was taken to the angiosuite for revascularization.

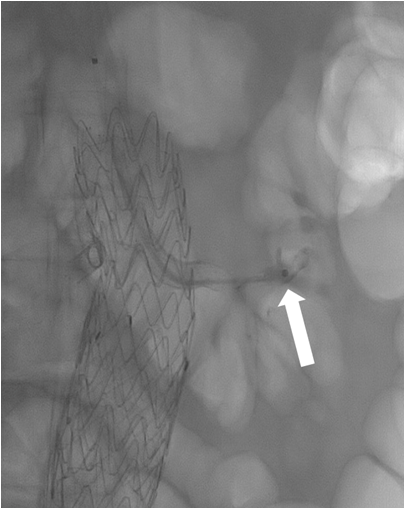

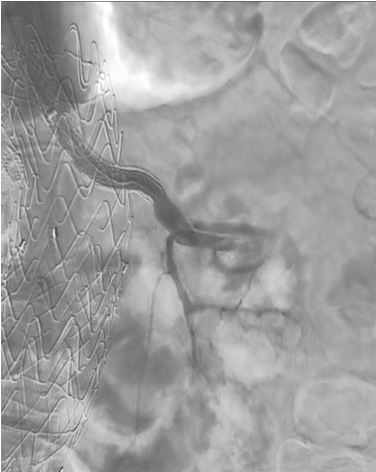

Under local anesthesia through percutaneous left brachial access, a McNamara catheter was placed to the left renal artery and we started an infusion with 100.000UI of urokinase per hour for 24 hours. Considering the ischemia time and only one previous functional kidney, the vascular team decided to carry on thromboaspiration and a stent-in-stent placement. Thromboaspiration was performed with an AXS Catalyst 6Fr catheter (Stryker Neurovascular, Mountain View, CA, USA) and the remaining thrombus was “pushed” into a terminal vessel (Fig. 2) to free collaterals and avoid a major percentage of parenchymal loss, then a B-graft 7x37mm and a 5x37mm (Peripheral Stent Graft System, Bentley Innomed, Hechingen, Germany) were placed. The final angiography showed patency of the stents, a free inferior polar artery, and a slow flow to the accessory vascularity (Fig. 3).

Figure 1: At the abdominal CT angiography it is possible to highlight the aortic endoprosthesis with renal stents with chimney technique and a filling defect in the distal main trunk of the left renal artery

Figure 2. During the interventional endovascular procedure a thromboaspiration was performed into the stent and renal artery with an AXS Catalyst 6Fr catheter and “pushing” maneuver

Immediately after, the patient underwent urgent dialysis.

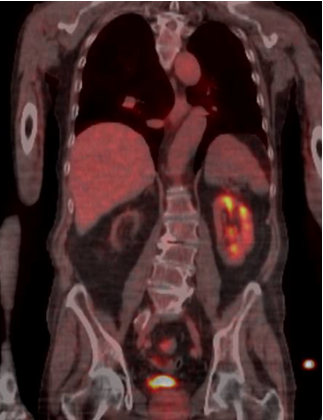

After 48-hours, the serum creatinine levels dropped to 2.3 mg/dl and the LDH to 250 U/L. The patient was discharged 3 days later with his basal renal function (1.8 mg/dl) without dialysis needed. After 6 months, the positron emission tomography (PET) control shows a functioning kidney (Fig. 4).

Discussion

COVID-19 is characterized by prolonged prothrombin time, high D-dimer, fibrinogen, factor VIII, and von Willebrand factor levels (2). Studies reported rates of venous thromboembolism and arterial thrombosis ranging around ∼7% in patients admitted to medical wards (3-5).

Endothelial dysfunction contributes to COVID-19-associated vascular inflammation, particularly endothelitis in the lung, heart, and kidneys; moreover, COVID-19 is associated with coagulopathy and microthrombi in the capillaries (7), and in our case, it is reasonable to assume that stent thrombosis may be due to the virus.

In situ renal artery occlusion is rare, but acute renal in-stent thrombosis is common, especially after complex endovascular treatments such as ChEVAR, visceral artery stenting is not free from complications depending on factors like smoking, antiplatelet therapy, stent type and follow-up. Prompt diagnosis is paramount to avoid permanent renal failure (8-10).

In a multicenter study in France, 201 patients underwent ChEVAR, and for 150, this was the first option technique. The primary patency of chimney stents was 97.4%, 96.7%, 95.2%, and 93.3% at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months respectively (10).

Figure 3. Completion angiogram showing the left renal artery stent patency and a free inferior polar artery

Figure 4. A 18-FDG-PET CT scan 6 months after the procedure involving thrombus aspiration and urokinase infusion in the renal stent showing a functional left kidney

The clinical picture is variable in patients with acute renal infarction. In 2004, Hazanov et al. identified 44 cases of renal embolus: 68% presented abdominal pain, 54% had hematuria and 93% had a serum LDH level > 400 U/dl and renal function was restored in patients treated up to 72 hours after the initial event (11). The differential diagnosis is urolithiasis, abdominal disease, lumbago, or myocardial infarction.

Timing for treatment is crucial, and thrombolytic therapy is not indicated after total renal occlusion.

Irreversible renal damage occurred when the main renal artery was occluded for more than 3 hours (12). Kidneys can tolerate 30–60 minutes of controlled clamp ischemia with mild structural changes and no acute functional loss (13).

Neurovascular devices are smaller compared to vascular devices; in our case it allowed not just the thromboaspiration, but to ‘‘push’’ distally the thrombus and free a collateral artery to save the remaining renal parenchyma. In the literature, one case describes thromboaspiration for acute renal thrombosis after renal stenting and another one describes the similar technique for acute renal embolism (14, 15). To our knowledge, this is the first case reported where thromboaspiration with neurovascular devices is used for revascularization of prolonged renal intra-stent artery thrombosis and it proved successful.

Conclusions

Because of the lack of evidence about the timing to treat intra-stent acute renal thrombosis, we suggest attempting renal revascularization with thromboaspiration and intraarterial thrombolysis, offering a safe method to restore renal function and save the remaining renal parenchyma. Despite the prolonged ischemia, we exemplify the potential benefits of an aggressive approach and hope this case helps to obtain a definitive protocol for diagnosis and treatment.

Ethics: Patient`s informed consent was obtained before all procedures

Peer-review: Internal and external

Conflicts of interest: None to declare

Authorship: study concept and design: F.M.O. and D.M., drafting of the manuscript: B.O.D. and F.M.O., study supervision: D.M., M.F. and A.I. Critical review: F.M.O., B.O.D., D.M., M.F. and AI

Acknowledgement and funding: None to declare

References

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

AUTHOR'S CORNER