Multidisciplinary Care for Patients with Cardiac Amyloidosis: a Lesson from the 2023 American College of Cardiology Expert Consensus

EDITORIALS

Multidisciplinary Care for Patients with Cardiac Amyloidosis: a Lesson from the 2023 American College of Cardiology Expert Consensus

Article Summary

- DOI: 10.24969/hvt.2023.388

- CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASES

- Published: 17/05/2023

- Received: 10/05/2023

- Accepted: 11/05/2023

- Views: 9044

- Downloads: 4549

- Keywords: Amyloidosis, heart disease, aged, frailty, multimorbidity, polipharmacology, ACC experts consensus

Address for Correspondence: Stefano Cacciatore, Department of Geriatrics and Orthopedics, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Rome, Italy. L.go F. Vito 1, 00168 Rome, Italy. E-mail: stefanocacciatore@live.it.

ORCID ID: 0000-0001-7504-3775

Carla Recupero1, Stefano Cacciatore1*, Marco Bernardi2, Anna Maria Martone3, Francesco Landi1,3

1Department of Geriatrics and Orthopaedics, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Rome, Italy.

2Department of Clinical, Internal Medicine, Anesthesiology and Cardiovascular Sciences, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy.

3Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS, Rome, Italy

Abstract

Amyloidosis is a rare and varied group of diseases defined by the misfolding, aggregation, and deposition of highly structured fibrils made of low molecular weight protein subunits known as amyloid deposits throughout different tissues. Depending on their form and location, amyloid deposits can produce a variety of clinical manifestations resulting in considerable morbidity, death, and a deterioration in quality of life. "Cardiac amyloidosis" refers to the clinical condition associated with cardiac amyloid infiltration of the heart. The American College of Cardiology has issued an expert consensus addressing cardiological management of cardiac amyloidosis, the need for an interdisciplinary approach to extra-cardiac manifestations and highlighting the importance of removing barriers to equitable care for patients with amyloidosis. In this editorial we summarize and discuss on relevant issues addressed in the consensus.

Key words: Amyloidosis, heart disease, aged, frailty, multimorbidity, polipharmacology, ACC experts consensus

Amyloidosis is a group of diseases defined by the misfolding, aggregation, and deposition of highly organized fibrils made of low molecular weight protein subunits known as amyloid deposits (1). The American College of Cardiology has issued an expert consensus on cardiological management of cardiac amyloidosis (CA), the need for an interdisciplinary approach to extra-cardiac manifestations, and the importance an equitable care (1). We summarize and comment on each of these key-points.

Definition and management of cardiac amyloidosis

CA is a restrictive cardiomyopathy caused by deposition of amyloid fibrils between myocardial fibers (1). The two most prevalent types are AL amyloidosis, caused by deposition of monoclonal immunoglobulin light chains, and ATTR subtype, due to transthyretin (TTR), a hormone-transporting carrier protein. Variant TTR amyloid cardiomyopathy (ATTR-CM) was formerly known as familial amyloidosis and is characterized by TTR gene replacement or deletion. Misfolding and aggregation of a genetically normal protein define wild-type ATTR-CM (1).

The prevalence of AL amyloidosis is 1/25,000, with an annual incidence of 1/75,000-100,000 (2), and 75% of individuals with AL have some degree of cardiac involvement (AL-CM) (3). In the case of ATTR-CM, research suggests that the condition is significantly more common than previously expected. Aging causes a rise in TTR misfolding and aggregation. ATTR amyloidosis generally affects people over the age of 60, and it is more frequent beyond the age of 70 (4, 5).

Clinical identification is delayed for the majority of CA patients. However, early detection is critical for providing effective therapy, improving survival, and/or preventing possibly irreparable loss of physical function and quality of life (1). CA symptoms and clinical findings are often non-specific. Increased left ventricular wall thickness (LVWT) may be misdiagnosed as hypertensive cardiomyopathy, aortic stenosis (AS)-related concentric hypertrophy, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, or other infiltrative illnesses.

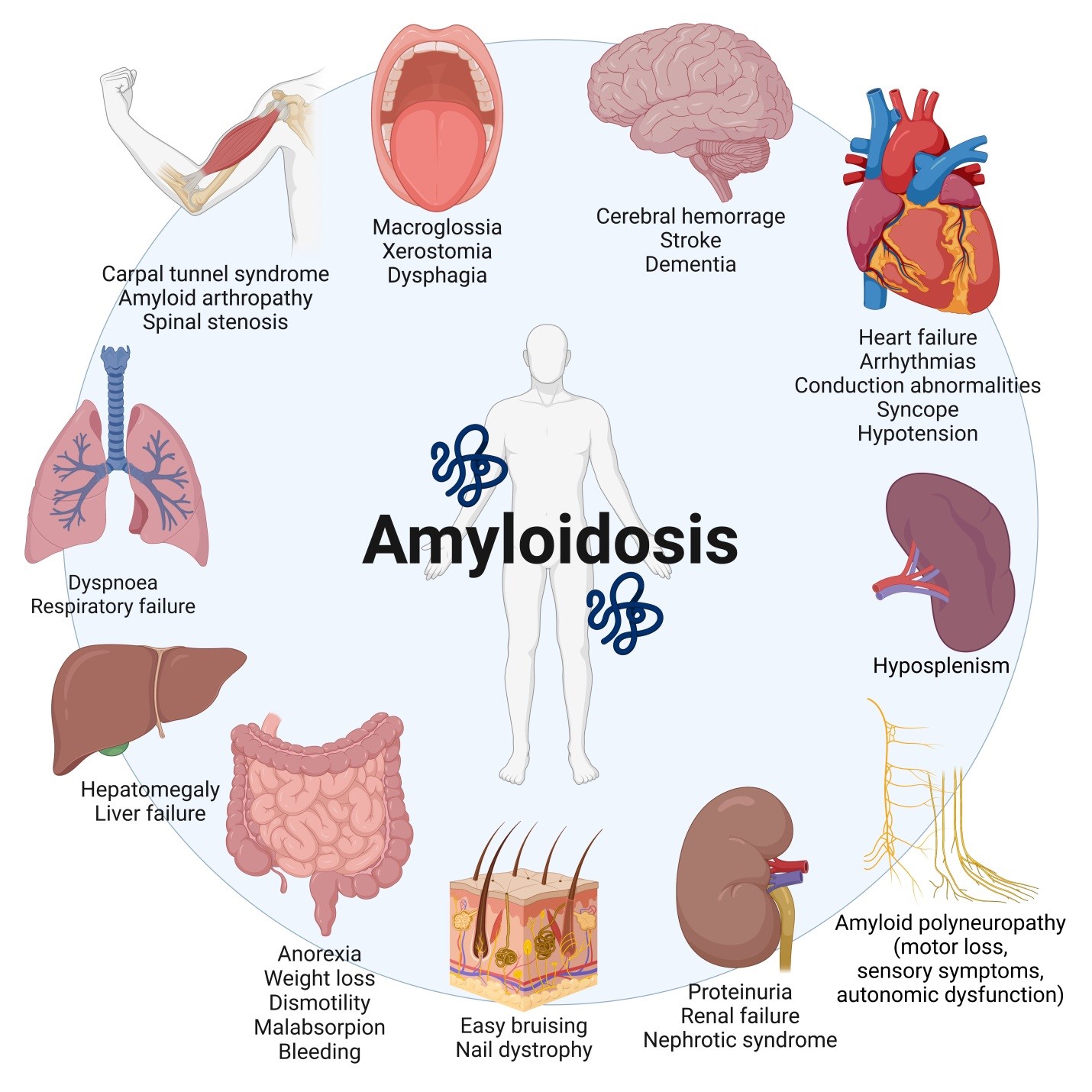

Figure 1. Cardiac and extracardiac manifestations of amyloidosis (Created with BioRender.com).

CA is usually linked to AS or heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) (5-10). As a result, diagnostic tests for such illnesses should take overlapping CA into account (1).

Before doing particular laboratory and imaging procedures, a high level of clinical suspicion is essential. “Red flags” associated with CA are both cardiac and extracardiac. The first include increased LVWT without hypertension or valvular heart disease, symptoms of heart failure (HF), diastolic dysfunction, atrial fibrillation (AF), conduction system disease, and rise of cardiac biomarkers. Extracardiac features include a wide range of manifestations affecting several organs (Fig. 1) (1, 11).

To rule out AL-CM, the diagnostic algorithm should always begin with a monoclonal protein study (MPS). Electrocardiography and transthoracic usually suggest the possibility of CA. Echocardiography can estimate the likelihood of CA versus other hypertrophic phenotypes in addition to determining the severity of cardiac involvement (12). Ultrasonographic findings include increased LVWT, diastolic dysfunction, reduced mitral annular systolic velocity, biatrial enlargement, and decreased global longitudinal strain with relative apical sparing. Discordance between QRS voltage and wall thickness is a common sign, but its absence doesn't rule out the possibility (13). Cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) and bone scintigraphy significantly improved diagnostic procedures (12). CA may be distinguished from other types of cardiomyopathies characterized by increased LVWT and preserved ejection fraction using cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR). CMR, on the other hand, cannot tell the difference between AL-CM and ATTR-CM. Technetium-pyrophosphate can be used for cardiac scintigraphy using single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT). A qualitative and quantitative scoring system based on the absorption of these radiotracers has been devised to aid in the diagnosis of ATTR-CM (14). SPECT, however, cannot rule out ATTR-CM and AL-CM (1, 15). Before the invention of cardiac scintigraphy, the tissue biopsy was the only technique able to identify CA. Endomyocardial biopsy should be performed if other tissue biopsy does not confirm amyloidosis, when there is a high clinical suspicion of CA in a patient with a monoclonal spike and/or serum free light chain K/L ratio above the upper limit, or if SPECT is not available (1, 16).

Tafamidis is the only medicine authorized for the treatment of ATTR-CM by the US Food and Drug Administration. It functions as a TTR stabilizer by delaying TTR dissociation and, as a result, fibril production and cardiac deposition. Early detection is critical since tafamidis slows disease development but does not always result in regression (17).

The cornerstone of CA therapy is volume control (1, 18). Loop diuretics and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists should also be considered. Because of the increased risk of overdiuresis, hyponatremia, hypokalemia, and renal dysfunction, thiazide diuretics (such as metolazone) should be taken with caution. Because patients with CA have a restricted euvolemic window due to diastolic dysfunction or restrictive physiology, kidney function is used to stage ATTR-CM, and increasing diuretic dose is associated with poor outcomes. Even at modest dosages, beta blockers may be poorly tolerated, and withdrawal may produce better results. Angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and angiotensin receptor blockers may be poorly tolerated in patients with underlying autonomic orthostatic hypotension owing to vasodilation (1, 18).

AF is frequent both in AL-CM and ATTR-CM. CA patients are more likely to develop intracardiac thrombi, even those on chronic anticoagulant medications (1, 19). As a result, anticoagulation is recommended regardless of the CHA2DS2-VASc score. Direct oral anticoagulants have been extensively used as first-line anticoagulation, however there is insufficient evidence from randomized clinical studies to support their use compared to warfarin in CA (1).

Multidisciplinary interventions for extra-cardiac manifestations

Diagnostic and clinical management of amyloidosis may benefit from the intervention of several specialists. Genetic testing may be necessary both for a complete evaluation of ATTR-CM and in counseling for at-risk relatives (1). Amyloid deposits can occur in a variety of organs (Fig. 1) (11). A significant proportion of amyloidosis patients develop amyloid neuropathy (17-35%), which manifests as sensory involvement (numbness, decreased balance, hypoesthesia), motor loss, or autonomic dysfunction. Amyloid angiopathy can result in cerebral hemorrhages as well as cognitive impairment. Carpal tunnel syndrome, spinal stenosis and radiculopathy, and amyloid arthritis are all caused by musculoskeletal involvement. Mucosal, neuropathic, or vascular involvement may lead to gastrointestinal symptoms. The interaction of amyloid nephropathy, cardiomyopathy, and autonomic neuropathy affects renal function. Finally, plasma cell dyscrasia may be the underlying cause for AL amyloidosis (10-40%) (1).

In addition, multiorgan involvement and poor prognosis make patients with amyloidosis highly complex. As a result, in addition to other specialists, a geriatrician might play an important role in identifying geriatric syndromes (20), managing symptoms and directing therapy according to the patient’s preferences and expectations (20, 21) – from early stages to terminal disease.

Removing barriers to equitable care

High drug costs and restricted access to specialists, according to the authors, are hurdles to fair care for individuals with amyloidosis. Because of the complexities of health-care systems and the variability of health-care expenses across different countries, advanced methods of diagnosis and treatment may be difficult for everyone to access. Potential techniques for lowering patient expenses involve enrolling more individuals in clinical trials and improving evaluation to identify patients who would benefit more from one treatment over another. In terms of accessibility, the authors propose telemedicine as a method of increasing the availability of professionals (1). However, although this strategy may be promising, it has several limitations owing to inexperience, limited resources, and possible social frailty in older individuals (22). An alternative could be to enhance territorial management and train all-rounded specialists such as cardiologists and geriatricians who can assess frailty and manage patients more effectively (23). However, the keystone concept is the assumption that CA should not be neglected since it is a common disease and responsible for mortality and a significant decrease in health and psychological wellbeing. Greater knowledge of its characteristics, diagnosis, and treatment alternatives is needed, in accordance with algorithms published by scientific societies. The ultimate goal should be to improve symptoms, survival, and quality of life.

Peer-review: Internal

Conflicts of interest: None to declare

Authorship: All authors have participated in manuscript design and drafting. All authors read and approved the final version.

Funding: None to declare. The authors have not declared a specific grant for this work from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgement: The authors thank Dr. Luis Esse for providing valuable insights on clinical and scientific subjects.

References

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

AUTHOR'S CORNER