Comparison of the clinical profile and outcomes of Covid-19 infection in vaccinated and unvaccinated people

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE

Comparison of the clinical profile and outcomes of Covid-19 infection in vaccinated and unvaccinated people

Article Summary

- DOI: 10.24969/hvt.2024.478

- Page(s): 208-212

- CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASES

- Published: 15/04/2024

- Received: 30/01/2024

- Revised: 31/03/2024

- Accepted: 31/03/2024

- Views: 4214

- Downloads: 3268

- Keywords: COVID-19, vaccination status, outcomes, disease severity, mortality

Address for Correspondence: Ramya Gadam, Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Government General Hospital, Rangaraya Medical College, Kakinada, India

Email: g.ramya1208@gmail.com Mobile:+93 9505455995

Sridevi Ganesan, V. Surya Kumari, Ramya Gadam

Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Government General Hospital, Rangaraya Medical College, Kakinada, India

Abstract

Objective: Vaccinating people can be an effective way of controlling the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic because vaccines have shown high efficacy in preventing serious illness and hospitalization. However, the long-term effectiveness of the vaccines is still unknown. Vaccines are not fully effective as evidenced by the reports of fully vaccinated people who developed COVID-19 infection.

The aim of the study was to compare the clinical profile and outcomes of the COVID 19 infection among vaccinated and unvaccinated patients.

Methods: The observational study was conducted from March to May 2023 at tertiary care center, Kakinada, India.

Results: In this study out of 56 COVID-19 infected patients, frequency of COPVID-19 according to age distribution was higher in 41 to 50 years of age population. There was no significant sex preponderance. Out of 56, most common presenting symptoms were breathlessness 37 (66%). Out of 56, 51 (91%) patients were vaccinated (Covisheild, Serum Institute India PVT LTD, India), remaining were not vaccinated. Out of 56, 35 {62%) patients had comorbidities. Out of 56, 44(79 %) patients presented with bilateral multiple opacities on chest X- Ray. Out of 56, 36 patients` saturation was maintained on room air which constitutes (64%). Out of 56, 36(64%) patients presented with mild disease severity. Out of 56, 10 patients succumbed to death of whom 7 (70%) patients were vaccinated , 3 (30%) patients were unvaccinated (p>0.05).

Conclusion: Although the vaccination does not restrict/avoid infections, it appears to protect the vaccinated people from severe forms of COVID 19 infections.

Key words: COVID-19, vaccination status, outcomes, disease severity, mortality

Introduction

Since the start of the pandemic, COVID-19 infection has resulted in 9.4 million deaths worldwide resulting in one of the major global health crises of the 21st century (1). Covid-19 has contributed to enormous adverse impact globally (2).Vaccinating people can be an effective way of controlling the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic because vaccines have shown high efficacy in preventing serious illness and hospitalization (3, 4). Vaccinations against coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) have undoubtedly conferred widespread protection against infection worldwide and are strongly associated with prevention of serious illness, with a hospitalization rate 10.5 times higher in unvaccinated compared with fully vaccinated persons (3 ,4).

However, the long-term effectiveness of the vaccines is still unknown. India has started its largest free vaccination drive in January 2021 (5). Initially vaccination was performed in health care workers.

This study aimed to determine clinical profile and outcomes in vaccinated and unvaccinated patients with COVID-19.

Methods

An observational study was done to compare the clinical profile and outcomes of the Covid 19 infection among vaccinated and unvaccinated patients admitted in COVID ward from March 2023 to May 2023 in tertiary care center, Kakinada, India. Patients with symptoms like breathlessness, cough, chest pain and fever, patients with recent travel history, patients with COVID real time polymerase chain reaction (RTPCR) positive test, patients older 12 years were included in the study.

![]()

Ethics approval of local Ethic Committee was obtained and patient consent was taken.

Patients age, symptoms, vaccination status, radiological profile, course of the disease were taken into consideration.

Vaccination was made using CovisheildTM vaccine (Serum Institute India PVT LTD, India), 2 doses 12-16 weeks apart.

X-ray was taken for all patients, saturation was recorded with pulse oximeter and ABG was sent for hypoxic patients. Based on AIIMS/ICMR joint monitoring group patients were classified as having mild, moderate and severe forms of disease.

Based on clinical, radiological and grading patient were kept on oxygen, non-invasive ventilation and mechanical ventilation.

Statistical analysis was done using Chi-square test.

Results

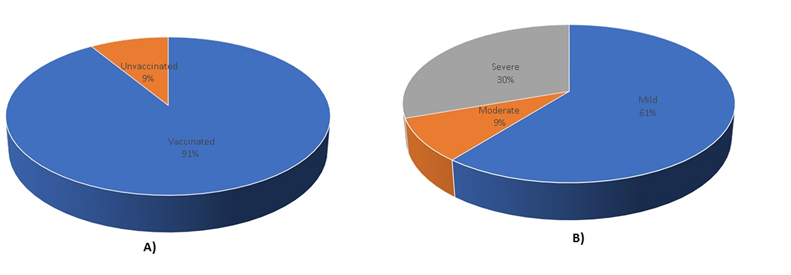

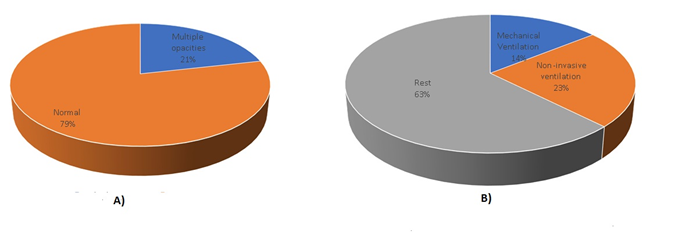

In this study out of 56 COVID-19 infected patients, frequency COVID-19 according to age distribution was higher in 41 to 50 years of age, which constitutes 23% of sample size (Table 1). There was no significant sex preponderance. Of 56, 51 (91%) patients were vaccinated with Covisheild vaccine. remaining 5 (9%) were not vaccinated (Fig. 1). In out of 56 patients, the most common presenting symptoms were breathlessness 37 (66%) followed by fever 35(63 %), and cough 30(54 %). Out of 56, 44 (79 %) patients presented with bilateral multiple opacities on chest X- ray, 12 (21%) patients do not have significant abnormalities on their X rays (Fig. 2). Out of 56, 35 (62%) patients have co-morbidities, 21 (38%) patients do not have comorbidities. Mild disease was detected in 61%, moderate in 9% and severe in 30% of patients (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Distribution of patients by vaccination status and severity of COVID-19 disease

Figure 2. Chest X-Ray findings (multiple opacities) and percentage of patients on noninvasive and mechanical ventilation

![]()

|

Table 1. Clinical characteristics |

||

|

Variables |

Number of patients (n=56) |

Percentage (%) |

|

Demographic characteristics |

||

|

Sex |

||

|

Male |

30 |

54 |

|

Female |

26 |

46 |

|

Age, years |

||

|

<20 |

5 |

9 |

|

21-30 |

8 |

14 |

|

31-40 |

7 |

13 |

|

41-50 |

13 |

23 |

|

51-60 |

9 |

16 |

|

61-70 |

9 |

16 |

|

71-80 |

5 |

9 |

|

Vaccination status |

||

|

Vaccinated |

51 |

91 |

|

Unvaccinated |

5 |

9 |

|

Symptoms |

||

|

Breathlessness |

37 |

66 |

|

Cough |

30 |

54 |

|

Fever |

35 |

63 |

|

Nausea & Vomiting |

3 |

5 |

|

Abdominal pain |

2 |

4 |

|

Body pain |

2 |

4 |

|

Headache |

3 |

5 |

|

Chest pain |

8 |

14 |

|

Comorbidities |

||

|

Comorbidities |

35 |

62 |

|

No Comorbidities |

21 |

38 |

|

Disease severity |

||

|

Mild |

34 |

61 |

|

Moderate |

5 |

9 |

|

Severe |

17 |

30 |

Analysis of association of clinical signs and disease severity demonstrated that patients with severe disease had higher comorbidities (p=0.028), lower oxygen saturation (p=0.017) and multiple opacities on chest X-Ray (p=0.005).

Patients with and without vaccination did not differ by demographics, symptoms or comorbidities, and hemodynamic parameters (p>0.05).

Out of 51 vaccinated, mild form of disease was seen in 35 patients who maintained saturation on room air, moderate form of disease was seen in 5 patients who maintained saturation with non-rebreathing mask and non-invasive ventilation and finally severe form of disease was seen in 11 patients who were mechanically ventilated (Table 2). Out of 5 unvaccinated patients, mild form of disease was seen in 1 patient who maintained saturation on room air, moderate form of disease was seen in 1 patient who maintained saturation with non-invasive ventilation and severe form of disease was seen in 3 patients who were mechanically ventilated. Overall severe form of disease has tendency to be higher in unvaccinated as compared to vaccinated (60% vs 21.6%, p=0.09).

Out of 56, 10 patients succumbed to death out of which 7 (70%) patients were vaccinated and having severe form of disease, 3 (30%) patients were unvaccinated who were having severe form of disease. Out of 7 vaccinated patients who were succumbed to death, 1 patient had history of paraquat (herbicide intake results in acute lung failure) intake one week prior to testing COVID-19 positive, 1 patient had severe pancreatitis and 1 patient had poliomyelitis deformity. Mortality rate was 60% in unvaccinated and 13.7% in vaccinated (p=0.85).

|

Table 2. Outcomes of patients according to vaccination status |

|||

|

Variables |

Vaccinated (n=51) |

Unvaccinated (n=5) |

p |

|

Disease severity |

|||

|

mild |

35 (68.6) |

1 (20) |

0.09 |

|

moderate |

5 (9.8) |

1 (20) |

|

|

severe |

11 (21.6) |

3 (60) |

|

|

Mortality |

|||

|

Alive |

44 (86.3) |

2 (40) |

0.85 |

|

Death |

7 (13.7) |

3 (60) |

|

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that disease severity was associated with comorbidities, low oxygen saturation and multiple opacities on chest X-Ray in hospitalized patients with COVID -19 who received and did not receive COVID-19 vaccine prior to hospitalization. We did not find the association of disease severity with demographic data, symptoms and hemodynamic data. Similar we did not find association of demographic and clinical signs with vaccination status. Analysis of in-hospital outcomes according to vaccination status demonstrated the tendency to higher disease severity in unvaccinated patients (p=0.09) and higher mortality though difference in latter did not reach statistical significance.

In our study, most common age group was 41-50 years with no gender preponderance. Breathlessness was the most presenting symptom, which was same as in study by Ramachandran et al (6). Overall, 79% of our patients presented with bilateral opacities on chest X-ray which is in accordance with the results of the study conducted by Martinez Chamorro et al (7). In majority of our patients, saturation was maintained with room air. Patients were categorized of having mild, moderate and severe forms of disease based on AIIMS/ ICMR joint monitoring group.

In our study 91% were vaccinated with Covisheild 2 doses in 2021, the gap between 2 doses is 12-16 weeks. In vaccinated group, most of patients had mild and moderate forms of disease that confirms previous studies (8-11) and in-hospital mortality in 91% vaccinated was 13% whereas 9% were unvaccinated in whom mortality was 60%, the latter also confirms in part previously reported data on mortality (12, 13).

Study limitations

Several limitations should be acknowledged as small sample size therefore we could interpret as tendencies for main outcomes in vaccinated and unvaccinated patients. It is worth mentioning this is a single hospital study.

![]()

Conclusion

The clinical outcomes of patient with COVID-19 were different among the vaccinated and unvaccinated patients with most of unvaccinated patients suffered from severe form of COVID-19 disease and had higher mortality. Although the vaccination may not protect from the disease it appears to protect the vaccinated people from progressing to severe forms of COVID-19 disease.

Ethics: Informed consent was obtained from patients before all procedures, Study protocol was approved local Ethic Committee.

Peer-review: Internal

Conflict of interest: None to declare

Authorship: S.G., V.S.K., R.G. equally contributed to the study, preparation of manuscript and fulfilled authorship criteria

Acknowledgement and funding: None to declare

References

| 1.World Health Organization. Weekly Operational Update on COVID-19 January 2022. WHO 2022; 1-10. | ||||

| 2.World Health Organization clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) when COVID-19 disease is suspected. Interim guidance. Pediatria I Medycyna Rodzinna 2020: 16: 9-26. https://doi.org/10.15557/PiMR.2020.0003 |

||||

| 3.Tenforde MW, Self WH, Adams K, Gaglani M, Ginde AA, McNeal T, et al. Association between mRNA vaccination and COVID-19 hospitalization and disease severity. JAMA 2021; 326: 2043-54. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.19499 https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.19499 PMid:34734975 PMCid:PMC8569602 |

||||

| 4.Havers FP, Pham H, Taylor C.A, Whitaker M, Patel K, Anglin O, et al. COVID-19 associated hospitalizations among vaccinated and unvaccinated adults 18 years or older in 13 US states, January 2021 to April 2022. JAMA Intern Med 2022; 182: 1071-81. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.4299 https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.4299 PMid:36074486 PMCid:PMC9459904 |

||||

| 5.Kumar VM, Perumal SRP, Trakht I, Thyagarajan SP. Strategy for COVID-19 vaccination in India: The country with the second highest population and number of cases. NPJ Vaccines 2021; 60. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-021-00327-2 PMid:33883557 PMCid:PMC8169891 |

||||

| 6.Ramachandran A. Clinic-radiological profile and outcome of severe COVID 19 patients at a tertiary care in Andhra Pradesh. IJMSCR 2021; 4: 663-73 | ||||

| 7.Chamorro EM, Diez Tascon A, Ibanez Sanz L, Ossaba Velez S, Borruel Nacenta S. Radiological diagnosis of patients with COVID-19. Radiologia 2021; 63: 56-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rx.2020.11.001 PMid:33339622 PMCid:PMC7685043 |

||||

| 8.Mohd A.A., Kamraju m. A study on COVID-19 vaccination drive in India . BRISC j Educ Res 2021;1: 76-9. | ||||

| 9.Pramod S, Govindan D, Ramasubramani P, Kar SS, Aggarwal R, and JIPMER vaccine effectiveness study group. Effectiveness of Covisheild vaccine in preventing COVID-19-A test-negative case control study. 2022; 40: 3294-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.02.014 PMid:35168838 PMCid:PMC8825308 |

||||

| 10.Tsundue T, Namdon T, Tsewang T, Topgyal S, Dolma T, Lhadon D, et al. First and second doses of vaccine provide high level of protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection in highly transmissible setting: results from a prospective cohort of participants residing in congregate facilities in India. BMJ Glob Health 2021; 7: e008271. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-008271 PMid:35609920 PMCid:PMC9130647 |

||||

| 11.Notarte KI, Catahay JS, Velasco JV, Pastrana A, Ver AT, Pangilinan FC, et al. Impact of COVID-19 vaccination on the risk of developing long-COVID and on existing long-COVID symptoms: A systematic review. EclinicalMedicine 2022; 53: 101624 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101624 PMid:36051247 PMCid:PMC9417563 |

||||

| 12.Zheng C, Shao W, Chen X, Zhang B, Wang G, Zhang W. Real world effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines: a literature review and metaanalysis. Emerg Microb Infect 2022; 11: 2383-92. https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2022.2122582 PMid:36069511 PMCid:PMC9542696 |

||||

| 13.Zontarctor A, Shivaprakash S, Tiwari A, Setia MS, Gianchandani T. Effectiveness of COVID-19 (Covishield TM and Covaxin) vaccines in health care workers in Mumbai, India: a retrospective cohort analysis. PLoS One 2022; 17: e0276759. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0276759 PMid:36301977 PMCid:PMC9612509 |

||||

Copyright

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

AUTHOR'S CORNER