Exploring precipitants of re-coarctation in coarctation of the aorta patients

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE

Exploring precipitants of re-coarctation in coarctation of the aorta patients

Article Summary

- DOI: 10.24969/hvt.2024.505

- Page(s): 382-390

- CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASES

- Published: 22/08/2024

- Received: 09/05/2024

- Revised: 30/07/2024

- Accepted: 31/08/2024

- Views: 4059

- Downloads: 3059

- Keywords: Aortic coarctation, heart defects, congenital, postoperative complications, cardiac surgery procedures

Address for Correspondence: Bobur Turaev, Department of Pediatric Cardiac Surgery, Clinics of Tashkent Pediatric Medical Institute, S.Yusupov street 7, Yunusabad, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Address for Correspondence: Bobur Turaev, Department of Pediatric Cardiac Surgery, Clinics of Tashkent Pediatric Medical Institute, S.Yusupov street 7, Yunusabad, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Email: tbb1991@mail.ru Phone: +998977038777

ORCID: Bobur B. Turaev – XXXX-XXXX-XXXX-XXXX, Khakimjon K. Abralov - XXXX-XXXX-XXXX-XXXX

Nodir Sh. Ibragimov - XXXX-XXXX-XXXX-XXXX

Bobur B. Turaev1, Khakimjon K. Abralov2, Nodir Sh. Ibragimov1

1Department of Pediatric Cardiac Surgery, Clinics of Tashkent Pediatric Medical Institute, Yunusabad, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

2Department of Congenital Heart Defects, Republican Specialized Scientific Practical Center of Surgery named after V.Vahidov, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Abstract

Objective: Coarctation of the aorta (CoA) is a congenital heart defect characterized by a narrowing of the aorta, often necessitating surgical repair to restore normal blood flow. Despite successful initial interventions, a significant subset of patients experiences recoarctation (re-CoA), the reoccurrence of aortic narrowing, presenting a considerable clinical challenge. This study aims to investigate the triggers or contributing factors associated with the development of re-CoA following the initial repair of CoA, to identify potential strategies for its prevention and management.

Methods: A retrospective cohort study includes information about 120 patients, who underwent 4 different types of surgical repairs of CoA through left thoracotomy between 2012-2022. Recoarctation was evaluated using the pressure gradient on the coarctation site measured by echocardiography. A threshold of more than 20mmHg was employed to define recoarctation. All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software.

Results: The study revealed that 30 patients (25%) experienced early recoarctation, while 52 patients (43.7%) encountered late recoarctation. Patient-related variables such as age, height, weight, gender, and body mass index (BMI) were not correlated with early or late recoarctation. Among the 28 patients (23.3%) who had arch hypoplasia, 12 of them experienced early recoarctation, and 22 of them exhibited late recoarctation. Correlation tests demonstrated a strong negative correlation of the Z-score of the arch size with both early recoarctation (r=-0.229, p=0.013) and late recoarctation (r=-0.421, p<0.001). Resection and end-to-end anastomosis (EEA) displayed the highest proportions of early (59%) and late (77%) recoarctation. Prosthetic patch aortoplasty (PPA) showed a relatively higher rate of recoarctation, with 27% of patients experiencing early recoarctation and 44% exhibiting late recoarctation. Resection and extended end-to-end anastomosis displayed a comparatively lower rate, with 0% experiencing early recoarctation and 23% exhibiting late recoarctation.

Conclusion: Aortic arch hypoplasia emerges as a significant factor for both early and late recoarctation. Additionally, while all coarctation repair methods carry some risk of recoarctation, resection and end-to-end anastomosis and prosthetic patch aortoplasty may pose a higher risk compared to extended end-to-end anastomosis. Recognizing these factors is crucial for optimizing surgical outcomes and reducing recoarctation incidence in patients with coarctation of the aorta.

Key words: Aortic coarctation, heart defects, congenital, postoperative complications, cardiac surgery procedures

Introduction

Coarctation of the aorta (CoA) is a congenital heart defect characterized by a narrowing of the aorta, typically near the insertion of the ductus arteriosus.

While significant strides have been made in improving the outcomes of CoA repair, the occurrence of recoarctation (re-CoA) poses a formidable challenge, warranting a meticulous exploration of its prevalence, associated risk factors, and subsequent management.

Graphical abstract

Understanding the prevalence of re-CoA is essential for gauging the success of surgical interventions and developing targeted postoperative care strategies. Current literature suggests a variable incidence of re-CoA, ranging from 5% to 30% across different cohorts (1, 2). This broad range underscores the complexity of factors influencing recoarctation dynamics, prompting the need for a nuanced examination of contributing variables.

In this study, we aim to investigate the prevalence of early and late recoarctation after surgical repair of CoA, identify significant risk factors, and evaluate the impact of different surgical techniques on its incidence.

Methods

Study design and population

A retrospective cohort investigation was conducted wherein medical records and computed tomography (CT) scans were retrospectively analyzed. Pertinent data, including intraoperative procedures, intraoperative and postoperative complications, and CT scan measurements, were gathered and recorded in an Excel spreadsheet for subsequent statistical analysis. Patient information and CT scan measurements were separately documented in distinct Excel sheets to minimize performance and detection bias.

The study included 120 patients diagnosed with isolated CoA who underwent elective surgical repair over the past decade. The study revealed that out of 120 patients who underwent surgical repair for CoA, 30 patients (25%) experienced early re-CoA, and 52 patients (43.7%) encountered late re-CoA. This means that 38 patients (31.3%) did not develop either early or late re-CoA, serving as the control group.

Given that clinical audits entail no deviation from standard clinical management, patient consent or formal ethical review/approval was not required; thus, the present study was registered as a clinical audit, and all data were de-identified. However, all patients provided informed consent for medical examinations and surgeries. Because of the study was retrospective it did not require approval of Ethics Committee.

Baseline variables

Patient related factors, such an age, gender, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), and results of medical examinations, such echocardiography (EchoCG) and CT scan findings were collected from hospital notes.

Echocardiography

All echocardiography (EchoCG) examinations, including coarctation site measurements, functions of heart valves and left ventricle, were conducted in accordance with established guidelines (3).

Computed tomography

Preoperative CT scans were scrutinized, and measurements were conducted utilizing "Syngo via ProtoNeo" software (Siemens Healthcare GmbH/Siemens Medical Solutions USA, 2018), adhering to the Society for Vascular Surgery guidelines and reporting standards (4).

The diameter of the aorta was measured at five distinct anatomical points: the ascending aorta, the aortic arch, the isthmus (typically corresponding to the site of CoA), the descending aorta, and the aorta at the level of the diaphragm. Following the acquisition of these measurements, Z-scores were calculated for all data points to standardize the values and facilitate comparative analysis.

Surgery

The patients underwent four different types of surgical procedures:

- Resection and end-to-end anastomosis (EEA): This technique involves the surgical removal (resection) of the narrowed segment of the aorta, followed by directly connecting (anastomosing) the two healthy ends of the aorta together.

-Aortoplasty using patch (PPA): In this technique, a patch (often made of synthetic material or the patient’s own tissue) is sewn into the aorta to enlarge the narrowed area.

-Resection and extended end-to-end anastomosis (EEEA): Similar to EEA, this technique involves resection of the narrowed segment. However, the resection extends further along the aorta, allowing for a more comprehensive removal of the affected segment. The healthy ends are then connected-Interposition using tube graft (PIG): This technique involves replacing the narrowed section of the aorta with a synthetic tube graft. The narrowed segment is removed, and the graft is sewn into place to bridge the gap.

Evaluation of recoarctation

Early re-CoA is defined as the recurrence of aortic narrowing shortly after the initial surgical repair of CoA, typically within the first few weeks to months post-surgery. Late recoarctation is defined as the recurrence of aortic narrowing long after the initial surgical repair, often identified during follow-up visits years after the initial procedure. In our investigation, recoarctation was evaluated using the pressure gradient on the coarctation site measured by EchoCG. A threshold of more than 20mmHg was employed to define recoarctation, aligning with the recommendations of various authors and guidelines (1, 5). Early recoarctation was characterized by a pressure gradient exceeding 20 mmHg during the initial examination after the operation, typically conducted during the hospital stay. Late recoarctation, on the other hand, was identified when a pressure gradient beyond 20 mmHg was observed in follow-up examinations conducted one year post-operation.

Follow-up

Patient data encompassed preoperative medical examination results, including EchoCG and multislice computed tomography (MSCT) findings, postoperative hospital status with EchoCG results, and follow-up examination findings at 1 month and 1-year post-operation with EchoCG.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics 22.0 software (IBM, USA), checking for homogeneity (Levene's test) and normal distribution (QQ-plot). Mean and standard deviation (SD) summarized symmetrically distributed numerical variables, while median and inter-quantile range (IQR) described non-symmetric numerical variables. Chi-square test used for categorical (nominal and ordinal) variables, the comparing of means were performed using paired t-test or Wilcoxon signed-rank test for paired variables and independent t-test or Mann-Whitney U test for independent variables according to normality and homogeneity. Pearson correlation coefficient was utilized for correlation tests. A significance level of p < 0.05 was employed in this study.

Results

The study revealed that 30 patients (25%) experienced early recoarctation, while 52 patients (43.7%) encountered late recoarctation.

A correlation test conducted between early and late recoarctation demonstrated a robust positive correlation (r=0.644, p<0.001), indicating that individuals experiencing early recoarctation were more likely to exhibit late recoarctation as well.

The investigation into patient-related factors for these cohorts yielded the following results (Table 1): there

were no differences in demographic and anthropometric variables between patients with early and late coarctation and without recoarctation.

|

Table 1. Demographic and anthropometric variables |

||||||

|

Variables |

Early re-CoA (n=30) |

No early re-CoA (n=90) |

p |

Late re-CoA (n=52) |

No late re-COA (n=68) |

p |

|

Age, months |

116.0 (102.0) |

81.4 (125.0) |

0.177 |

77.4 (94.6) |

100.0 (137.0) |

0.336 |

|

Male sex, n(%) |

21 (70) |

64 (71) |

0.908 |

37 (71) |

47 (69) |

0.905 |

|

Height, m |

1.20 (0.40) |

0.985 (0.415) |

0.053 |

1.040 (0.398) |

1.040 (0.444) |

0.936 |

|

Weight, kg |

29.0 (23.4) |

20.7 (22.8) |

0.088 |

21.7 (21.2) |

23.8 (24.8) |

0.629 |

|

BMI, kg/m2 |

16.50 (4.33) |

15.6 (4.7) |

0.325 |

15.70 (3.88) |

16.00 (5.14) |

0.724 |

|

Data are presented as mean (SD) and n(%) BMI – body mass index, re-CoA - recoarctation |

||||||

Results of the occurrence of early and re-CoA within different age groups are shown in Table 2.

|

Table 2. The occurrence of early and re-coarctation status within different age groups |

||

|

Age groups (n=120) |

Patients with early re-CoA |

Patients with late re-CoA |

|

Group 1 (<1 year) (n=46), n(%) |

4 (8.7) |

19 (41) |

|

Group 2 (1-3 years) (n=15), n(%) |

4 (26.7) |

7 (46.6) |

|

Group 3 (3-10 years) (n=25), n(%) |

11 (44) |

14 (56) |

|

Group 4 (>10 years) (n=34), n(%) |

11 (32.3) |

12 (35) |

|

p |

0.006 |

0.358 |

|

Data are presented as n(%) re-CoA - recoarctation |

||

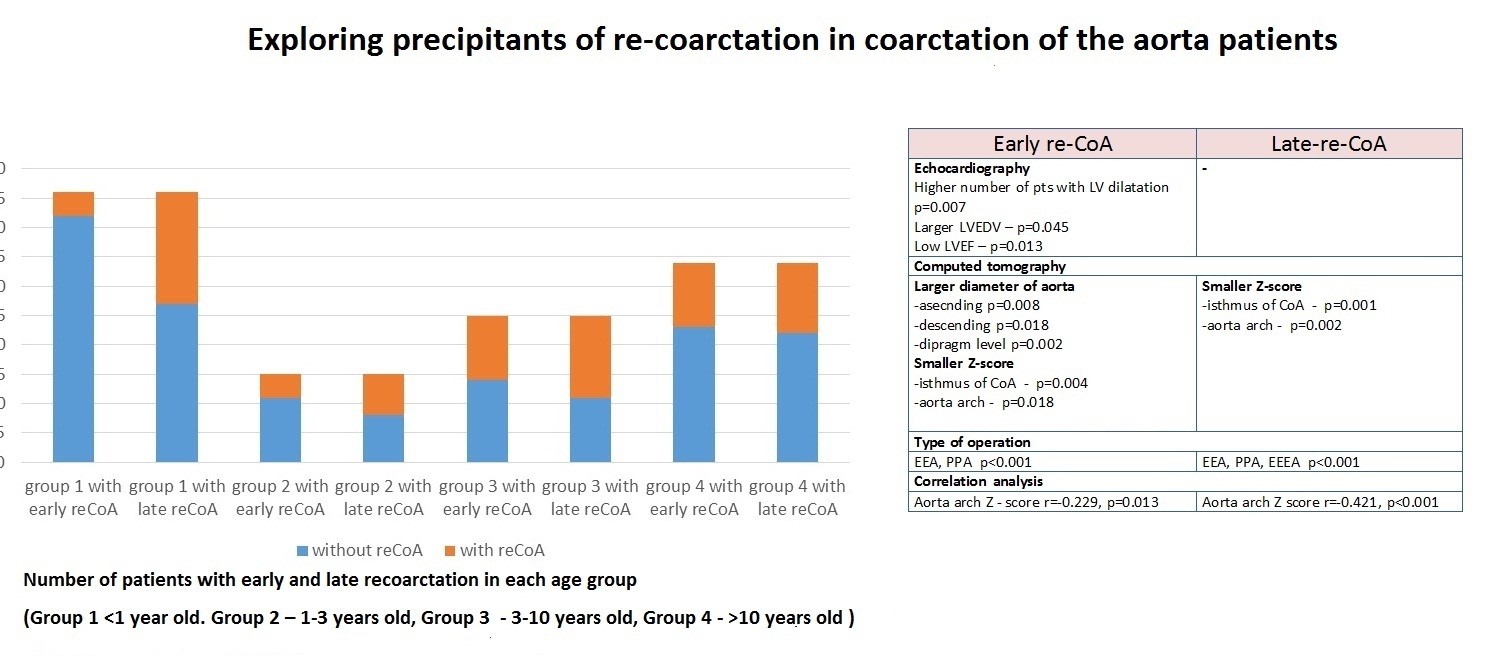

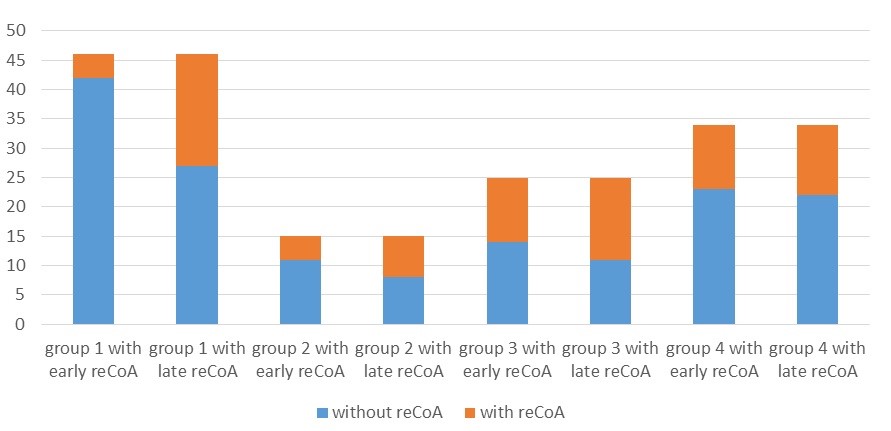

Figure 1. Number of patients with early and late recoarctation in each age group (Group 1 <1 year old. Group 2 – 1-3 years old, Group 3 - 3-10 years old, Group 4 - >10 years old )

reCoA - recoarctation

From the Table 2 and Figure 1, it is evident that the early re-CoA rate was significantly higher in older age groups compared to younger groups (p=0.006). However, the number of patients with re-CoA changed significantly in younger age groups, especially in patients less than one year of age, and the percentage of patients with late re-CoA did not differ significantly between age groups (p=0.358). Overall, in older patients, the risk of re-CoA is higher than in younger patients, but this proportion remained stable with time. Meanwhile, the proportion of patients with early re-CoA can be lower in younger patients, but this tends to increase over time. This finding requires further investigation to assess the factors that affect younger patients developing re-CoA later.

Analyzing the influence of pre-operative echocardiographic findings on the development of early and late re-CoA yielded the following results presented in Table 3.

|

Table 3. Influence of pre-operative echocardiographic findings on the development of early and late re-CoA |

||||||

|

Variables |

Early re-CoA (n=30) |

No early re-CoA (n=90) |

p |

Late re-CoA (n=52) |

No late re-CoA (n=68) |

p |

|

Pressure gradient on a CoA site, mmHg |

57.3 (19.3) |

52.8 (15) |

0.196 |

55.0 (17.0) |

52.9 (15.7) |

0.492 |

|

Mitral regurgitation, n (%) Without Mild Moderate Severe |

19 (63.3) 6 (20) 5 (16.7) 0 |

71 (78.9) 10 (11.1) 8 (8.9) 1 (1.1) |

0.160 |

35 (67.3) 9 (17.3) 8 (15.4) 0 |

55 (80.1) 7 (10.3) 1 (1.5) 4 (5.9) |

0.100 |

|

Tricuspid regurgitation, n(%) Without Mild Moderate Severe |

24 (80) 3 (10) 3 (10) 0 |

75 (83.3) 11 (12.2) 4 (4.5) 0 |

0.442 |

43 (82.3) 5 (9.6) 4 (7.7) 0 |

56 (82.4) 9 (13.2) 2 (2.9) 0 |

0.565 |

|

Aortic regurgitation, n(%) Without Mild Moderate Severe |

24 (80) 4 (13.3) 2 (6.7) 0 |

77 (85.5) 11 (12.2) 2 (2.3) 0 |

0.318 |

43 (82.7) 7 (13.4) 2 (3.9) 0 |

57 (83.8) 8 (11.8) 2 (2.9) 0 |

0.713 |

|

LV dilation, n(%) |

19 (63) |

32 (35.5) |

0.007 |

27 (51.9) |

23 (33.8) |

0.054 |

|

LVEDV, ml |

80.4 (49.9) |

64.2 (33.1) |

0.045 |

67.5 (43.7) |

68 (33.8) |

0.943 |

|

LVEF, % |

44.4 (23.0) |

56.1 (16.2) |

0.013 |

48.4 (22.2) |

46.9(22.0) |

0.721 |

|

Data are presented as mean (SD) and n(%) CoA - Coarctation, LV – left ventricle, LVEDV – left ventricular end-diastolic volume, LVEF – left ventricular ejection fraction |

||||||

Our initial hypothesis suggesting that the severity of aortic CoA influences the development of early and late re-CoA was not confirmed by statistical tests. The analyses revealed that only patients with left ventricular (LV) dysfunction, characterized by LV dilation, higher end-diastolic volume of the left ventricle (LVEDV), and lower ejection fraction of the left ventricle (LVEF), are related to early re-CoA (all p<0.05).

Additional comparison tests of CT scan findings that provide further insights into this topic are presented in the Table 4.

![]()

|

Table 4. Influence of pre-operative CT scan findings on the development of early and late re-CoA |

||||||

|

Variables |

Early re-CoA (n=30) |

No early re-CoA (n=90) |

p |

Late re-CoA (n=52) |

No late re-CoA (n=68) |

p |

|

Diameter of ascending aorta, mm |

21.7 (6.83) |

17.0 (8.17) |

0.008 |

18.3 (7.72) |

18.2 (8.48) |

0.968 |

|

Z-score of ascending aorta |

+2.13 (1.13) |

+1.69 (1.21) |

0.098 |

+1.76 (1.153) |

+1.83 (1.25) |

0.750 |

|

Diameter of aortic arch, mm |

14.2 (4.46) |

12.6 (5.86) |

0.215 |

11.9 (5.02) |

13.8 (5.87) |

0.073 |

|

Z-score of aortic arch |

-1.06 (1.91) |

-0.183 (1.54) |

0.013 |

-1.20 (1.74) |

+0.216 (1.35) |

<0.001 |

|

Diameter of isthmus (CoA site), mm |

4.66 (2.20) |

4.48 (2.82) |

0.766 |

4.23 (2.24) |

4.73 (2.96) |

0.348 |

|

Z-score of isthmus (CoA site) |

-6.11 (2.44) |

-4.64 (2.14) |

0.004 |

-5.82 (2.54) |

-4.44 (1.93) |

0.002 |

|

Diameter of descending aorta, mm |

14.5 (4.80) |

11.6 (5.71) |

0.018 |

12.3 (4.99) |

12.4 (6.12) |

0.886 |

|

Z-score of descending aorta |

+1.30 (1.19 |

+1.01 (1.47) |

0.362 |

+1.00 (1.12) |

+1.16 (1.59) |

0.576 |

|

Diameter of aorta at diaphragm level, mm |

14.2 (5.19) |

10.3 (4.25) |

0.002 |

12.0 (5.31) |

10.7 (4.39) |

0.192 |

|

Z-score of aorta at diaphragm level |

+1.45 (1.42) |

+0.715 (1.42) |

0.022 |

+1.15 (1.38) |

+0.731 (1.49) |

0.144 |

|

Data are presented as mean (SD) CoA - coarctation, CT – computed tomography, recoarctation – re-CoA |

||||||

As can be seen from Table 4, the diameters of ascending, descending aorta and aorta at diaphragm level (p=0.008, p=0.018, p=0.002, respectively) and Z-score at diaphragm level (p=0.02) were significantly higher in patients with early re-CoA as compared to control group. While Z-scores at aorta isthmus and arch level were markedly lower in early re-CoA group than in control group (p=0.004, p=0.013, respectively). Similarly, in late re-CoA group Z-scores at isthmus and arch level were significantly lower as compared to control (p<0.001, p=0.002).

Several factors, such as the size of the ascending and descending aorta, and the size and Z-score of the aorta at the diaphragm level, were initially considered to be influenced by age. However, upon closer examination, early re-CoA was found to occur more frequently in older age groups, and these factors became non-significantly different in the late re-CoA check. Only two variables remained significantly different, namely the z-score of the aortic arch and the z-score of the isthmus. Consequently, the z-score of the aortic arch and the z-score of the isthmus were significantly lower in patients with early and late re-CoA. Correlation tests demonstrated a strong negative correlation of the Z-score of the arch size with both early re-CoA (r=-0.229, p=0.013) and late re-CoA (r=-0.421, p<0.001).

Many authors have reported (1, 2, 5) that one of the main risk factors for re-CoA is the surgical technique employed. To assess the impact of different operation types on re-CoA, we compared the incidence of re-CoA among four distinct surgical groups (Table 5).

|

Table 5. Impact of different operation types on re-CoA |

||

|

Operation type groups (120 patients): |

Patients with early re-CoA |

Patients with late re-CoA |

|

Group I (EEA) (27 patients), n (%) |

16 (59) |

21 (77) |

|

Group II (PPA) (52 patients), n (%) |

14 (26.9) |

23 (44) |

|

Group III (EEEA) (35 patients), n (%) |

0 |

8 (23) |

|

Group IV (PIG) (6 patients), n (%) |

0 |

0 |

|

p |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

|

Data are presented as n(%) EEA - resection and end-to-end anastomosis, EEEA - resection and extended end-to-end anastomosis, PIG – resection and interposition using tube graft, PPA - aortoplasty using patch, re-CoA - recoarctation |

||

Heart, Vessels and Transplantation 2024; 8: doi: 10.24969/hvt.2024.505

Recoarctation after CoA repair Turaev et al.

![]()

The analysis revealed notable variations in the rates of re-CoA among different surgical techniques (p<0.001). Patients who underwent prosthetic interposition graft (PIG) did not exhibit any instances of early or late re-CoA. In contrast, resection and end-to-end anastomosis (EEA) displayed the highest proportions of early (59%) and late (77%) re-CoA. Prosthetic patch aortoplasty (PPA) showed a relatively higher rate of re-CoA, with 27% of patients experiencing early re-CoA and 44% exhibiting late re-CoA. Resection and extended end-to-end anastomosis displayed a comparatively lower rate, with 0% experiencing early re-CoA and 23% exhibiting late re-CoA.

The impact of operation types on rate oif re-CoA within distinct age groups are shown in Table 6.

|

Table 6. The impact of operation type within distinct age groups |

||||||||

|

Age groups, n(%) |

Operation type groups |

|||||||

|

Group I (EEA) |

Group II (PPA) |

Group III (EEEA) |

Group IV (PIG) |

|||||

|

Early re-CoA |

Late re-CoA |

Early re-CoA |

Late re-CoA |

Early re-CoA |

Late re-CoA |

Early re-CoA |

Late re-CoA |

|

|

Group 1 (<1 year) |

4 (33) |

8 (66.7) |

0 |

3 (60) |

0 |

8 (27.6) |

0 |

0 |

|

Group 2 (1-3 years) |

4 (80) |

4 (80) |

0 |

3 (75) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Group 3 (3-10 years) |

5 (71) |

6 (100) |

6 (37.5) |

8 (50) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Group 4 (>10 years) |

3 (100) |

3 (100) |

8 (29.6) |

9 (33.3) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Data are presented as n(%) EEA - resection and end-to-end anastomosis, EEEA - resection and extended end-to-end anastomosis, PIG – resection and interposition using tube graft, PPA - aortoplasty using patch, re-CoA - recoarctation |

||||||||

The Table 6 illustrates that early re-CoA predominantly occurred in older age groups, particularly in cases involving EEA and PPA. EEA demonstrated a higher rate of early re-CoA across all age groups, with a more pronounced increase in older groups from an early stage; while in younger groups, it exhibited a tendency to rise over time. PPA exhibited more favorable short-term results in younger groups; however, the proportion of re-CoA in these groups significantly escalated, reaching up to 75%. In contrast, in older groups, although short-term results might be less favorable, they did not worsen significantly over time. EEEA exhibited the best short-term results with 0% early re-CoA across all age groups. Nevertheless, in patients under 1 year of age, the proportion of late re-CoA reached up to 27.6%. It is important to note that the EEEA method was only applied to little children, and its performance in older populations remains unassessed.

Discussions

This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of re-CoA following surgical repair of CoA of the aorta (CoA), identify significant risk factors contributing to its development, and evaluate the impact of different surgical techniques on its occurrence. Our findings revealed that 25% of patients experienced early re-CoA, while 43.7% developed late re-CoA, underscoring the persistent challenge of managing CoA post-surgery.

The data in the table reveals that the mean age of patients with early re-CoA was higher compared to patients without early re-CoA. Intriguingly, the mean age at the time of the operation was lower in patients who later developed late re-CoA. However, a comparison test indicated no statistical significance. This implies that patient-related variables such as age, height, weight, gender, and BMI may not be causative factors in the development of early or late re-CoA.

The clinical significance of age at the time of repair in relation to re-CoA has been underscored in several studies (6, 7). Additionally, investigations encompassing various factors, such as weight before surgery, have yielded mixed findings (6-9). Some studies have suggested a noteworthy association between lower weight at the time of repair and arch restenosis (9).

However, the complexity of these associations becomes apparent when considering multivariable models. Notably, Gorbatykh et al. (8) observed that weight did not emerge as a significant risk factor when included in a multivariable model alongside different surgical strategies. Furthermore, contrasting perspectives have been presented regarding birth weight and body length at surgery as potential risk factors. While some studies posit lower birth weight (10) and smaller body length at surgery (11) as risk factors, our series challenges these assertions, suggesting that these factors may not be conclusive indicators of susceptibility to early or late re-CoA.

Our study demonstrated that LV dysfunction and dilatation on EchoCG and larger aorta size on CT play role in development of early re-CoA, while smaller Z-score at arch and isthmus level of aorta were found characteristic to our patients with early and late re-CoA. Among our patients the 28 patients (23.3%) who had arch hypoplasia, 12 of them experienced early re-CoA, and 22 of them exhibited late re-CoA. Interestingly, only 6 patients (21.4% of patients with arch hypoplasia) did not experience re-CoA. Correlation tests demonstrated a strong negative correlation of the Z-score of the arch size with both early re-CoA (r=-0.229, p=0.013) and late re-CoA (r=-0.421, p<0.001). Therefore, it can be concluded that arch hypoplasia is one of the main risk factors for the development of both early and late re-CoA.

Numerous studies (6-12) have explored the relationship between re-CoA and aortic arch morphometry. Conflicting results have been reported, with some studies identifying a hypoplastic aortic arch as a significant risk factor. Hager et al. (11) reported that the presence of a hypoplastic arch increased the odds of developing re-CoA or experiencing mortality by 2.9 to 1. However, Gorbatykh et al. (8) demonstrated that a hypoplastic arch did not remain a determinant factor when incorporated into a multivariable regression model alongside different types of surgical strategies. Intriguingly, McElhinney et al. (7) found that a smaller transverse arch diameter was associated with an elevated risk of re-CoA, and this effect was more pronounced when indexed to weight. Additionally, Burch et al. (12) concluded that for every 1-mm increase in the transverse arch diameter, the risk for re-CoA decreased by 43%. This collective evidence underscores the importance of considering hypoplastic aortic arch as a crucial risk factor for re-CoA when deciding on the optimal repair strategy.

While assessing the impact of different surgical methods on developing re-CoA, it is important to note that PIG surgery was considered a less risky group. However, this observation should be interpreted cautiously, as PIG was primarily performed in older patients whose growth had nearly concluded. Consequently, the lack of re-CoA in the PIG group may be attributed to limited patient growth, preventing the graft size from becoming insufficient. Therefore, while PIG demonstrated a lower risk in this specific context, it cannot be conclusively deemed a universally safe method for all patients. In summary, all methods of CoA repair carry some risk of re-CoA, but EEA and PPA appear to have a higher risk than EEEA.

Concerning the choice of surgical technique, the literature has emphasized that extended end-to-end anastomosis is considered a superior alternative for preventing re-CoA. This preference is attributed to the method's advantages, including a more extensive resection, preservation of the subclavian artery, and the use of an oblique anastomosis (13-15).

In the literature, the EEA method has been considered the most prone to re-CoA, with reported rates reaching as high as 86% (1, 5), while PPA showed similar results in infant patients. However, in older patients, the re-CoA rate after PPA was lower (1, 16). Across all methods, younger groups exhibited an increasing proportion of re-CoA over time. The primary surgical reasons for re-CoA are believed to include the following factors:

-Inadequate resection of all ductal tissues. Incomplete resection of the stenosis leads to the formation of thickened and nonelastic ends, hindering the growth of the anastomosis. Scarred walls with these characteristics are unable to undergo normal growth in subsequent years. Elzenga and Gittenberger's (17) research revealed that the CoA tissue and the adjacent portions of the aortic wall may contain ductal material, which, if not completely removed, poses a risk of restenosis. These histologic findings provide robust support for the hypothesis that every possible effort should be exerted to excise the constricting tissue and revert to the normal aortic wall, enabling growth at both ends. Therefore, methods of EEA and PPA showed higher risk of re-CoA, while in these methods there is high risk of leaving ductal tissue.

-Lack of growth of a suture line. The limited growth of a suture line has been identified as a potential factor contributing to increased pressure gradients on a CoA site, particularly in surgeries such as EEA and EEEA.

Consequently, some experts recommend considering the use of Prolene 7.0 or even Prolene 8.0 for infants in these procedures to mitigate the risk of re-CoA (18).

-Lack of growth of a hypoplastic transverse arch. The inadequate growth of a hypoplastic transverse arch has been substantiated by our preceding statistical analyses. Notably, Kotani et al. (19) reported a remarkable 90% freedom from reoperation at 3 years with EEEA, even in cases of severe hypoplastic aortic arch (z-value < − 6). Several other studies have consistently concluded that EEEA yields superior results in patients with hypoplastic aortic arch (1, 6). However, when we examined the impact of hypoplastic arch status across different operation methods, it became evident that patients with arch hypoplasia exhibited a high risk of late re-CoA in all methods: 100% in EEA, 75% in PPA, and 80% in EEEA among patients with hypoplastic arch. In summary, aortic arch hypoplasia emerges as a principal risk factor for re-CoA, and none of the employed surgical techniques provide complete mitigation for these patients.

Despite numerous studies comparing various surgical strategies (1, 5, 16), the evidence suggests that there is no universally superior technique, and the selection among them should be customized based on individual patient characteristics.

Study limitations

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. Firstly, the retrospective nature of the study may introduce selection bias and limit the ability to establish causal relationships. Additionally, we experienced loss to follow-up in some patients, which may affect the generalizability of our findings. Another limitation is that we included only patients with isolated CoA, excluding those with CoA and other congenital heart defects. Future research should address these limitations by including a broader patient population and employing prospective study designs to validate and extend our findings.

Conclusion

The patient-related demographic and anthropometric variables, including age, height, weight, gender, and BMI, suggests that these factors may not directly contribute to the development of early or late re-CoA. However, our findings indicate that aortic arch hypoplasia (lower Z-scores on CT) emerges as a significant risk factor for both early and late re-CoA, highlighting the importance of this anatomical characteristic in patient risk assessment and surgical planning.

Furthermore, while all methods of CoA repair carry inherent risks of re-CoA, our study suggests that certain surgical techniques may pose a higher risk than others. Specifically, resection and end-to-end anastomosis (EEA) and prosthetic patch aortoplasty (PPA) appear to be associated with a greater likelihood of re-CoA compared to extended end-to-end anastomosis (EEEA).

In summary, our findings underscore the complexity of re-CoA development and its multifactorial nature. Recognizing the significance of aortic arch hypoplasia and considering the differential risks associated with various surgical techniques are essential for optimizing patient outcomes and reducing the incidence of re-CoA in individuals with CoA of the aorta. Further research and ongoing surveillance are warranted to refine risk stratification strategies and improve the long-term management of patients undergoing surgical repair for CoA of the aorta.

Ethics: All patients provided informed consent for medical examinations and surgeries. Because of the study was retrospective it did not require approval of Ethics Committee

Peer-review: External and internal

Conflict of interest: None to declare

Authorship: B.B. T., K.K.A., and N.Sh.I. equally contributed to the study and manuscript preparation for publication and fulfilled all authorship criteria.

Acknowledgements and funding: None to declare

Statement on A.I.-assisted technologies use: Authors declared they did not use AI-assisted technologies in preparation of this manuscript

References

| 1.Backer CL, Mavroudis C. Coarctation of the aorta. In: Pediatric Cardiac Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia; PA, Mosby: 2014. pp. 840-4. | ||||

| 2. Dias M, Barros A, Leite Moreira A, Miranda J. Risk Factors for Recoarctation and Mortality in Infants Submitted to Aortic Coarctation Repair: A Systematic Review. Pediatr Cardiol 2020; 41: 561-75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00246-020-02319-w PMid:32107586 |

||||

| 3. Baumgartner H, Bonhoeffer P, DeGroot N, deHaan F, Deanfield J, Galie N, et al. Task Force on the Management of Grown-up Congenital Heart Disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC); Association for European Pediatric Cardiology (AEPC); ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG). Eur Heart J 2010; 31: 2915-57.. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehq249 PMid:20801927 |

||||

| 4.Chaikof E, Dalman R, Eskandari M. The Society for Vascular Surgery practice guidelines on the care of patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm J Vasc Surg 2018; 67: 2-77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2017.10.044 PMid:29268916 |

||||

| 5.Dodge-Khatami A, Backer C, Mavroudis C. Risk factors for recoarctation and results of reoperation: A 40-year review. J Card Surg 2000; 15: 369-377. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8191.2000.tb01295.x PMid:11678458 |

||||

| 6. Lehnert A, Villemain O, Gaudin R, Meot M, Raisky O, Bonnet D. Risk factors of mortality and recoarctation after coarctation repair in infancy Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2019; doi: /10.1093/icvts /ivz11 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acvdsp.2018.10.288 |

||||

| 7. McElhinney D, Yang S, Hogarty A, Rychik J, Gleason M, Zachary C, et al. Recurrent arch obstruction after repair of isolated coarctation of the aorta in neonates and young infants: is low weight a risk factor? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2021; 122: 883-90. https://doi.org/10.1067/mtc.2001.116316 PMid:11689792 |

||||

| 8. Gorbatykh A, Nichai N, Ivantsov S, Voitov A, Kulyabin Y, Gorbatykh Y, et al. Risk factors for aortic coarctation development in young children. Pediatria 2017; 96: 118-24. https://doi.org/10.24110/0031-403X-2017-96-3-118-124 |

||||

| 9.Soynov I, Sinelnikov Y, Gorbatykh Y, Omelchenko A, Nichay KIN, Bogachev-Prokophiev A, et al. Modified reverse aortoplasty versus extended anastomosis in patients with coarctation of the aorta and distal arch hypoplasia, Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2018; ; 53: 254-61. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejcts/ezx249 PMid:28977406 |

||||

| 10.Truong DT, Tani LY, Minich LL, Burch PT, Bardsley TR, Menon SC. Factors associated with recoarctation after surgical repair of coarctation of the aorta by way of thoracotomy in young infants, Pediatr Cardiol 2014; 35: 164-70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00246-013-0757-6 PMid:23852462 |

||||

| 11.Hager A, Schreiber C, Nutzl S, Hess J. Mortality and restenosis rate of surgical coarctation repair in infancy: a study of 191 patients. Cardiology 2009; 112: 36-41. https://doi.org/10.1159/000137697 PMid:18580057 |

||||

| 12.Burch P, Cowley C, Holubkov R, Null D, Lambert L, Kouretas P, et al. Coarctation repair in neonates and young infants: is small size or low weight still a risk factor?, J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009; 138: 547-52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.04.046 PMid:19698833 |

||||

| 13.Lansman AJ, A. J. Shapiro and M. S. Schiller, Extended aortic arch anastomosis for repair of coarctation in infancy Circulation; 74: 137-141, 1986. | ||||

| 14.Kaushal S, Backer CI, Patel JN. Coarctation of the aorta: midterm outcomes of resection with extended end-to-end anastomosis, Ann Thorac Surg 2009; 88: 1932-93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.08.035 PMid:19932265 |

||||

| 15.Thomson JD, Mulpur A, Guerrero R. Outcome after extended arch repair for aortic coarctation, Heart 2006; 92: 90-4. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2004.058685 PMid:15845612 PMCid:PMC1860999 |

||||

| 16. Backer CL, Paape K, Zales VR. Coarctation of the aorta. Repair with polytetrafluoroethylene patch aortoplasty. Circulation 1995; 92: 132-6. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.92.9.132 PMid:7586396 |

||||

| 17.Elzenga N, Gittenberger D, Groot A. Localised coarctation of the aorta. Br Heart J 1983; 49: 317-23. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.49.4.317 PMid:6830664 PMCid:PMC481306 |

||||

| 18. Minotti C, Scioni M, Castaldi B, Guariento A, Biffanti R, Di Salvo G, et al. Effectiveness of repair of aortic coarctation in neonates: A long-term experience. Pediatr Cardiol 2022; 43: 17-23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00246-021-02685-z PMid:34341850 PMCid:PMC8766375 |

||||

| 19.Kotani Y, Anggriawan S, Chetan D. Fate of the hypoplastic proximal aortic arch in infants undergoing repair for coarctation of the aorta through a left thoracotomy Ann Thorac Surg 2014; 98: 1386-93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.05.042 PMid:25152386 |

||||

Copyright

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

AUTHOR'S CORNER