Morphological characteristics of the perifocal zone of glial tumors of the brain

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE

Morphological characteristics of the perifocal zone of glial tumors of the brain

Article Summary

- DOI: 10.24969/hvt.2026.622

- CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASES

- Published: 18/12/2025

- Received: 29/08/2025

- Revised: 14/11/2025

- Accepted: 18/12/2025

- Views: 539

- Downloads: 198

- Keywords: Glial tumors, perifocal zone, morphology, perifocal edema, blood-brain barrier, invasion, microvascular density, morphometry

Address for Correspondence: Zhenishbek M. Karimov, Department of Neurology and Neurosurgery, S.B. Daniyarov Institute of qualification Training, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan

E-mail: k_jenishbek@mail.ru

ORCID: 0000-0003-4317-2649

Zhenishbek M. Karimov

Department of Neurology and Neurosurgery, S.B. Daniyarov Institute of qualification Training, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan

Abstract

Objective: The perifocal edema zone of glial tumors is an active morphofunctional compartment that determines the volume of vasogenic and cytotoxic edema, clinical symptoms, and resectability. Its morphology remains insufficiently standardized due to heterogeneous sample selection criteria and the lack of uniform semiquantitative scales for assessing the perifocal zone, a fact emphasized by recent reviews on the "non-enhancing" peritumoral area (NEPA) /PFZ.

The aim of this study was to characterize the cellular and tissue organization of the perifocal zone (PFZ) and identify tumor cell migration into the edema zone.

Methods: A single-center observational morphological study was conducted on 70 consecutive patients aged 25–65 years who underwent surgery for diffuse glial tumors (15 astrocytomas, 15 oligodendrogliomas, 10 anaplastic astrocytomas, 10 anaplastic oligodendrogliomas, and 20 glioblastomas). Primary diffuse gliomas with an accessible PFZ fragment and a complete MRI set were included. PFZ specimens were obtained along the macroscopically determined tumor border during standard resections. Stereological morphometry (microvessel density, perivascular space area, edema index) and selective electron microscopy were performed. The volume of the cerebral cortex was determined using semi-automated T2/FLAIR-MRI segmentation with a gradation of ≤30; 30–60; 60–100; ≥100 cm³; when available, rCBV/ADC and the DTI-ALPS index were also analyzed as a proxy for glymphatic function. Statistical analysis included the t-test/Mann–Whitney test, ANOVA/Kruskal–Wallis test, χ²/Fisher's exact test, Spearman/Pearson correlation.

Results: Perifocal edema in all morphological variants of gliomas was characterized by pericellular and perivascular edema, neuroglial loosening, and focal demyelination. The semiquantitative index of edema was the highest in glioblastoma (2.9 (0.2)) points) compared with astrocytoma (2.3 (0.2)) and oligodendroglioma (2.2 (0.2)), (p<0.01). Tumor cell invasion into the PFZ was absent in Grade II astrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas (0 points), was recorded in approximately half of the cases of anaplastic astrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas (1.5 (0.1) and 1.4 (0.1) points)) and was most pronounced in glioblastomas (2.9 (0.1)) points, (p<0.01). Vascular reaction, microgliosis, and lymphocytic-leukocytic infiltration showed a similar gradient with maximum values in glioblastoma (all ≥2.7 (0.1)) points, (p<0.05). The total score of morphological changes in the PFZ was 7.8 (0.6) in low-grade gliomas, 11.4–11.5 (0.9) in anaplastic tumors, and 16.8 (0.7) in glioblastoma (p<0.01 vs Grade II; p<0.05 vs anaplastic forms) and positively correlated with a PFZ volume ≥60 cm³ and less favorable functional outcomes (p<0.05). Based on the morphological profile, angiogenic, inflammatory-reactive, and mixed morphotypes of the PFZ were distinguished; The mixed type was more often associated with a PFO volume ≥60 cm³ and worse early outcomes (mRS/KPS at discharge).

Conclusion: The perifocal zone (PFZ) of gliomas is an active morphofunctional compartment with a gradient of tumor cell invasion, vascular remodeling, glial reactivity, and immune infiltration from low-grade gliomas to glioblastoma. Semiquantitative assessment of microvascular density, perivascular space area, and invasion severity in the PFZ can serve as the basis for partially standardizing the morphological description of the perifocal zone and stratifying resectability, residual tumor volume, and recurrence risk.

Key words: Glial tumors, perifocal zone, morphology, perifocal edema, blood-brain barrier, invasion, microvascular density, morphometry

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Despite numerous studies of changes in the surrounding tissue of brain tumors, there is no single term for the area of infiltration and edema; the terms "peritumoral zone," "perifocal edema zone," and others are used (1, 2). In this study, the term perifocal zone (PFZ) is used as the broadest, encompassing low-intensity contrasting infiltrative tissues and vasogenic/cytotoxic components of edema, which is important for stratifying resectability and interpreting the "non-enhancing" peritumoral area (NEPA) on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (2–8). The PFZ is an active morphofunctional compartment with a combination of microvascular remodeling, increased permeability, pericyte reduction, and disruption of endothelial tight junctions (claudin-5/occludin/ZO-1), which are key links in the dysfunction of the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and the gliovascular unit (5, 9). At the glial level, reactive astro- and microgliosis and loss of aquaporin-4 (AQP4) polarity with endothelial swelling are characteristic (6, 9); the molecular profile of the PFZ includes overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and proinflammatory mediators, including interleukin-6 (IL-6) (7, 9). Current approaches to assessing the non-enhancing portion of the tumor and the extent of resection emphasize the importance of the PFZ for treatment outcomes (3, 8). Additional imaging techniques, including diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and analysis along the perivascular space (ALPS), indicate the contribution of glymphatic dysfunction to edema formation (10,12,13).

Its morphology remains insufficiently standardized due to heterogeneous sample selection criteria and the lack of uniform semiquantitative scales for assessing the perifocal zone, a fact emphasized by recent reviews on NEPA/PFZ.

The aim of the study was to characterize the cellular and tissue organization of the perifocal zone of glial brain tumors and evaluate tumor cell invasion into the perifocal edema zone.

Methods

Study design and population

The study was conducted as a single-center observational study at the Neurosurgery Clinic of the National Hospital under the Ministry of Health of the Kyrgyz Republic and the laboratory of the Department of Pathological Anatomy of the I.K. Akhunbaev Kyrgyz State Medical Academy from 2023 to 2025. The analysis included 70 consecutively operated patients with glial tumors (39 men, 31 women; 25-65 years old). For morphological analysis, the WHO classification was used. The histological diagnosis was established in accordance with the WHO central nervous system (CNS) 2021 classification (3). Distribution by histotypes: astrocytoma - 15 observations; oligodendroglioma - 15; anaplastic astrocytoma - 10; anaplastic oligodendroglioma - 10; glioblastoma - 20.

Inclusion criteria: primary diffuse gliomas; availability of a complete MRI set; availability of a fragment of the PFZ.

Exclusion criteria: other CNS diseases (tumors of other histogenesis, traumatic brain injury, stroke, infections), poor-quality or insufficient sample volume, severe coagulation artifact, prolonged sample ischemia greater than 30 minutes from excision to fixation, failure to comply with fixation standards.

The study protocol was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the M. Mamakeev National Surgical Center of the Ministry of Health of the Kyrgyz Republic. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2024), ICH GCP, and national requirements. Written informed consent was obtained. Perifocal tissue samples were obtained during standard surgeries without increasing the resection volume; the data were de-identified and anonymized.

Baseline variables

All patients underwent a standard clinical and neurological examinations with collection of demographic, laboratory and neurological evaluation data.

Magnetic resonance imaging

All patients underwent brain MRI with T1, FLAIR, DWI, and proton MR spectroscopy sequences. The studies were performed on a 3.0 T MR scanner using a 32-channel phased-array head coil (Philips Achieva 3.0T TX). T2/FLAIR segmentation of the PFZ was performed semiautomatically with expert mask review by two independent specialists. Volumetric grading of the perifocal destructurized tissue (PFD): ≤30; 30–60; 60–100; ≥100 cm³. When available, relative cerebral blood flow (rCBV), adsorption diffusion coefficient (ADC), and the DTI-ALPS index were additionally assessed.

RANO resect categories were used to classify the extent of resection: class 1 (suramaximal resection) — no residual contrast-enhancing nodule and ≤5 cm³ of residual non-enhancing (T2/FLAIR) tissue; then classes 2–4 according to increasing residual tumor volume (11,14,15). Pre- and postoperative volumes of contrast-enhancing and non-enhancing tumor components (cm³) were recorded in the protocol.

Perifocal tissue sample collection during surgery and morphological analysis

PFD tissue samples were obtained along the tumor margin during resections. Destructurized tissue adjacent to the tumor nodule was collected for morphological analysis; these fragments easily disintegrated and were washed away with a stream of saline. Samples were collected from an area adjacent to the macroscopically defined tumor border, with subsequent marking of the tumor's location. Fixation was performed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for 24–48 hours, followed by post-processing and paraffin embedding. The 4-μm-thick sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

Morphological features of the PFZ were assessed using light microscopy on a three-point scale:

0 – absent; 1 – mild; 2 – moderate; 3 – severe.

The following features were assessed:

1. Perifocal edema;

2. Tumor cell invasion;

3. Reactive changes in astrocytes and oligodendrogliocytes;

4. Vascular reaction;

5. Microglial response;

6. Lymphocyte/leukocyte infiltration.

Visual fields were selected using systematic random sampling. Microvessel density (MVD; number of vascular lumens/mm²), perivascular space area (PVS; % of field area), and edema index (% of clear lacunae) were calculated in ImageJ/FIJI (NIH, USA) using stereology plugins. Micrometer calibration was performed. To assess intra- and interobserver variability, 10% of slides were reanalyzed, and the coefficient of variation and Cohen's κ were calculated. Morphological parameters were compared with tumor grade, T2/FLAIR tumor volume, and clinical and functional outcomes.

Treatment

Pre- and postoperatively, patients received anti-edema therapy as clinically and instrumentally indicated, including glucocorticosteroids and osmotic diuretics. After stabilization, all patients were discharged with minimal neurological deficit and referred for further chemoradiation.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in IBM SPSS Statistics v21.0 (IBM Corp., USA) and R v4.x. Continuous data were presented as mean (SD) or median (IQR) if not normally distributed (Shapiro-Wilk test). For comparison of independent groups, the t-test or Mann–Whitney test, ANOVA, or Kruskal–Wallis test were used; categorical variables were compared using the χ² test or Fisher's exact test.

Correlation analysis was performed using Spearman's rank order (primary method) and Pearson's rank order for normal distribution. The significance level was p<0.05.

Results

General characteristics of perifocal edema

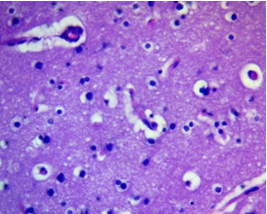

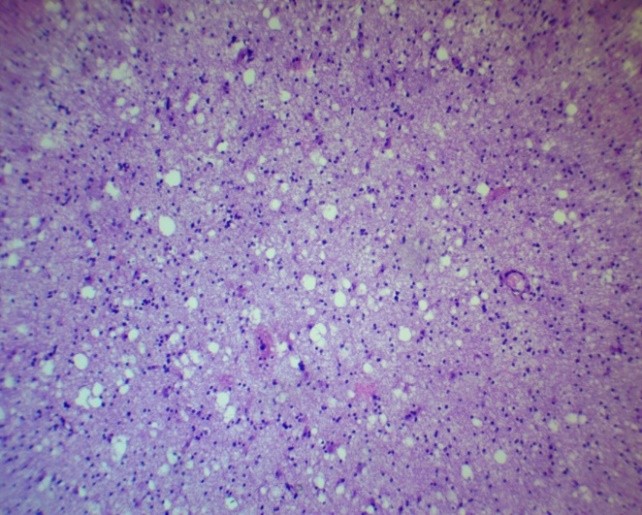

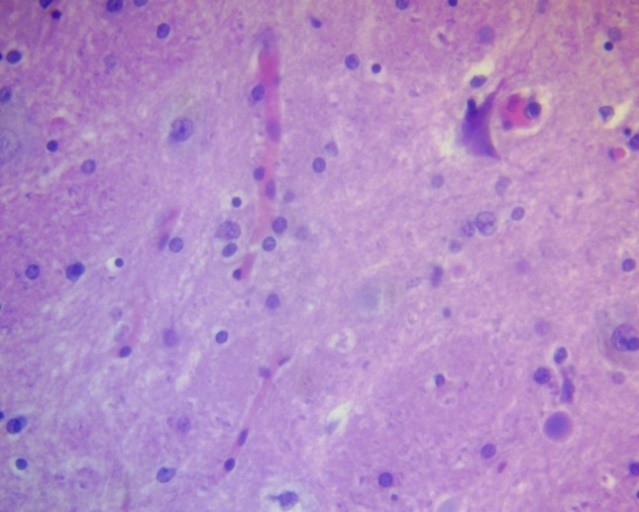

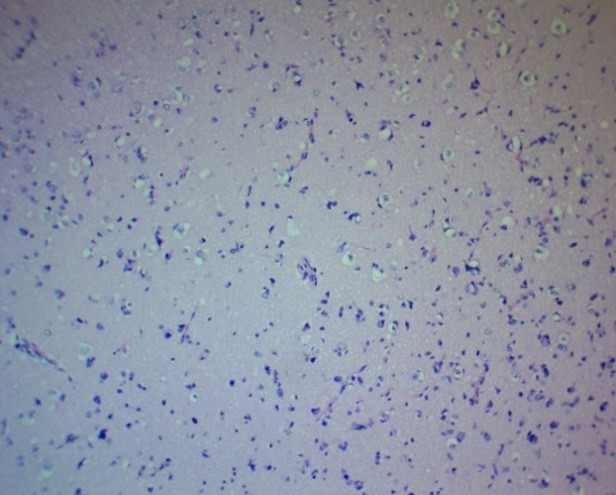

Perifocal edema was a key morphological and pathophysiological manifestation in the area surrounding glial brain tumors. It was characterized by pronounced destructive and degenerative changes, including voids around cells (pericellular edema) and vessels (perivascular edema). Pericellular and perivascular edema resulted from increased BBB permeability under the influence of proinflammatory cytokines, particularly VEGF, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor- α (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Pericellular and perivascular edema of astrocytoma H&E, ×400

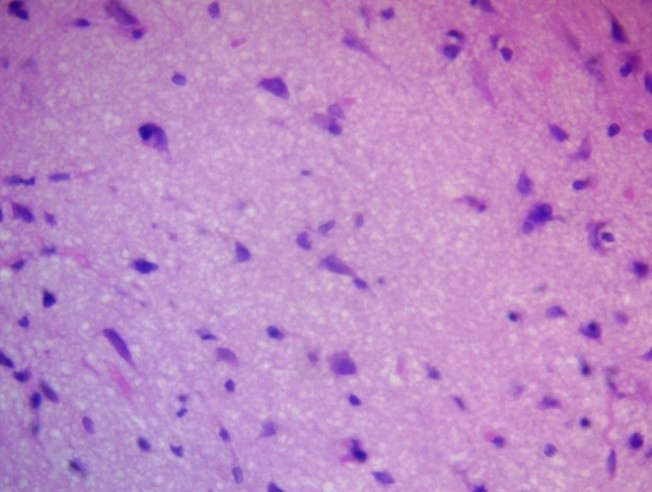

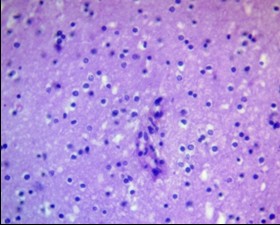

Neuroglial rarefaction and loss of cellular density (decrease in the number of cells per a certain area), especially astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, were noted in limited areas, which could reflect both vasogenic and cytotoxic nature of the edema (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Pericellular zone of anaplastic astrocytoma Areas of tissue rarefaction. H&E, ×400.

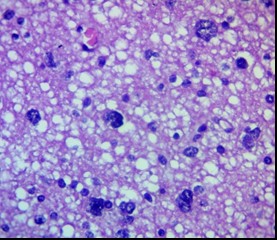

Porous or spongy structures were formed, visible by light microscopy as areas with multiple lacunae and uneven staining, indicating degradation of the extracellular matrix (Fig. 3).

Tumor cell invasion into the perifocal zone.

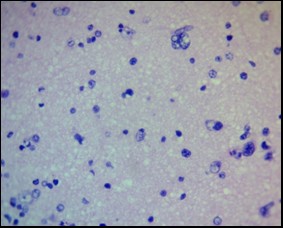

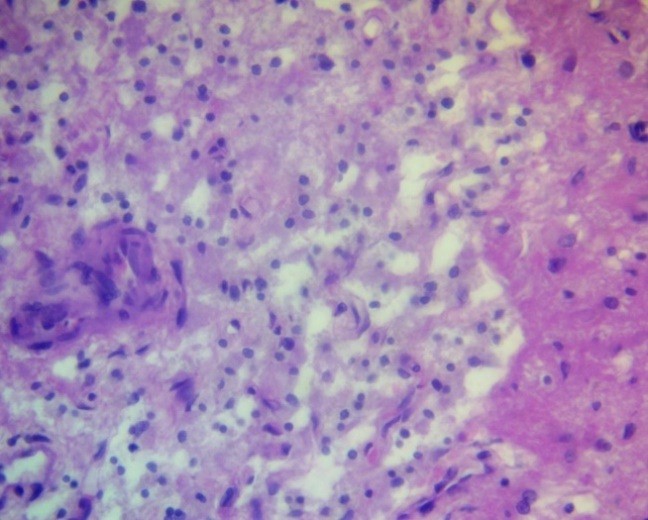

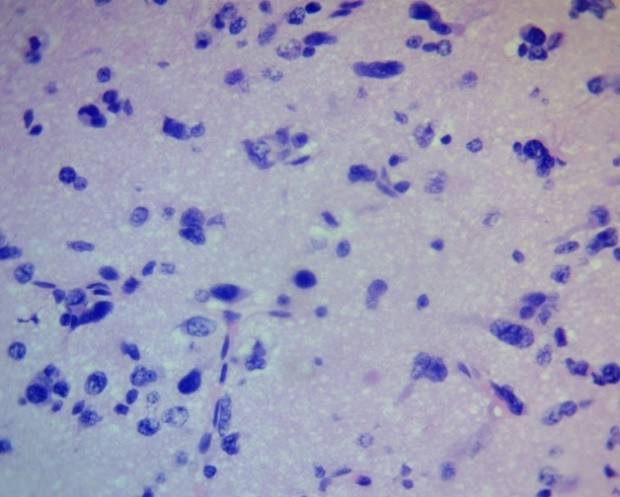

Tumor cell invasion into the perifocal zone was a key distinction between low-grade and high-grade gliomas and reflected the degree of tumor aggressiveness. In diffuse astrocytomas (WHO Grade II) and low-grade oligodendrogliomas, morphologically verifiable tumor cells were generally not detected in the perifocal zone, which was confirmed by both H&E staining and immunohistochemistry. In cases of anaplastic astrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas (Grade III), the appearance of single tumor cells in the outer portions of the PFZ was observed, predominantly in the form of scattered, diffuse microscopic clusters localized perivascularly or subpially (Fig. 4).

Figure 3. Peripheral zone of glioblastoma. Honeycomb structures (ECM degradation). H&E, ×100.

Figure 4. Peripheral zone of anaplastic oligodendroglioma. Single invasive cells. H&E, ×400

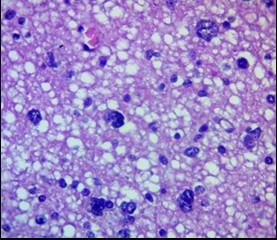

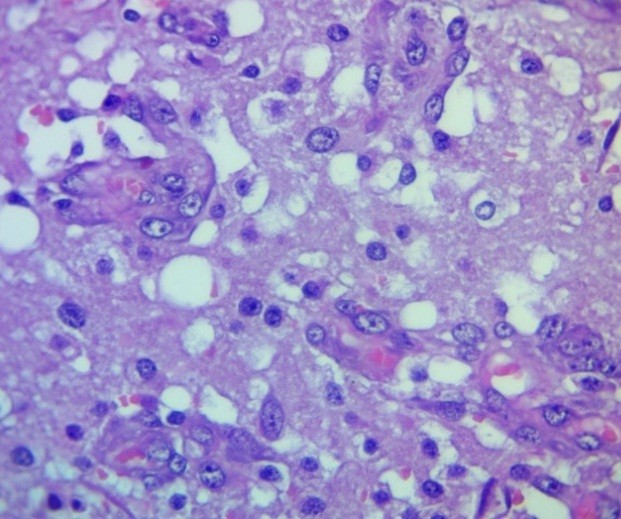

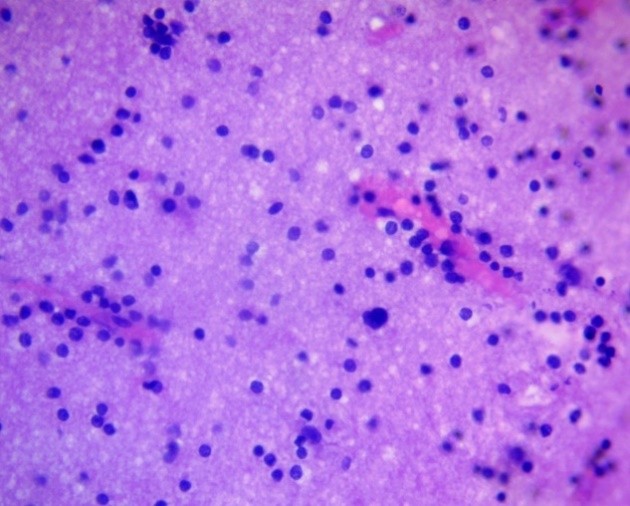

The most pronounced invasion was recorded in glioblastomas (Grade IV), especially in the giant cell and gliosarcomatous variants. In all analyzed cases, massive tumor cell infiltration of all layers of the PFZ, including the deep layers and subcortical structures, was detected (Fig. 5). Invasion along vessels, in white matter, and subependymally was frequently noted, which may correlate with the phenomenon of tumor "flow" along tracts according to diffusion tensor MRI data. The use of dual-staining immunohistochemistry (e.g., GFAP/Ki-67 or Nestin/SOX2) allows the detection of tumor elements in the PFZ and the assessment of their proliferative activity and stem-like properties.

Reactive changes in glial cells

Changes in astrocytes and oligodendrogliocytes in the peripheral zone of glial tumors were predominantly reactive in nature and reflected the glial tissue's response to edema, hypoxia, and metabolic depletion. In low-grade astrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas (Grade II), moderate cytoplasmic edema of astrocytes and oligodendrogliocytes, degenerative changes with vacuolization, nuclear pyknosis, hyperplasia, and hypertrophy of astrocytes with increased prominence of their processes were observed in the peripheral zone of astrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas (Fig. 6).

In tumors of a higher malignancy grade (anaplastic astrocytoma, anaplastic oligodendroglioma Grade III, glioblastoma Grade IV), the morphological picture was more severe: necrotic astrocytes and oligodendrogliocytes were noted, especially in areas of severe ischemic damage or capillary compression, pronounced mitochondrial degeneration, vacuolization and disintegration of nucleoli according to electron microscopy data.

Figure 5. Peripheral zone of glioblastoma. Massive tumor cell infiltration. H&E, ×400.

Figure 6. Peripheral zone of astrocytoma. Moderate glial cell reactivity. H&E, ×400.

The formation of granular balls (corpora amylacea), interpreted as products of metabolic exhaustion and glial degeneration, as well as binucleated and multinucleated cells, which required differential diagnosis with tumor gliocytes (Fig. 7), was observed. Current data suggest that reactive astrocytes in the PFZ participate in the regulation of fluid homeostasis through increased AQP4 expression and the redistribution of these channels from a typical perivascular location to a more diffuse one, which may contribute to impaired fluid drainage and worsening edema.

Vascular reaction

The vascular reaction in the PFZ of glial tumors was characterized by varying degrees of proliferative changes in endothelial and pericyte cells, including the formation of structures morphologically resembling vascular "glomeruli" (convolutes). This reaction is considered a component of a local adaptive mechanism aimed at compensating for impaired metabolism, draining tumor breakdown products, and stabilizing microcirculation.

In low-grade tumors such as astrocytoma and oligodendroglioma, vascular changes were minimal and represented primarily by mild endothelial cell proliferation without significant pericyte involvement (Fig. 8).

Figure 7. Glioblastoma PFZ. Gliocyte necrobiosis, "granular balls." H&E, ×400.

PFZ – perifocal zone

Figure 8. Oligodendroglioma PFZ. Weak endothelial proliferation. H&E, ×400.

PFZ – perifocal zone

In cases of anaplastic astrocytoma and anaplastic oligodendroglioma, vascular proliferation increased: hyperplasia and hypertrophy of both endothelial and pericyte elements were observed, with the formation of initial vascular glomeruli (Fig. 9).

Figure 9. Peripheral zone of anaplastic astrocytoma. Endothelial/pericyte proliferation. H&E, ×400.

The most pronounced changes were observed in glioblastoma, where active proliferation of endothelial cells and pericytes, the formation of mature vascular glomeruli, and the development of neoangiogenesis zones against a background of extensive areas of necrosis were observed in all cases (Fig. 10).

Figure 10. Peripheral zone of glioblastoma. "Tangles"/neoangiogenesis. H&E, ×400.

Morphologically, the microglial response was manifested by an increase in the number of microgliocytes, their hypertrophy, and transformation into granular (amoeboid) forms, as well as perivascular aggregation with the formation of "granular balls" that perform phagocytic and barrier functions. In astrocytoma and oligodendroglioma, a predominantly mild to moderate proliferation of microgliocytes was observed, without signs of pronounced activation (Fig. 11).

Figure 11. Oligodendroglioma PFZ. Moderate microglial proliferation. H&E, ×100.

PFZ – perifocal zone

In samples of anaplastic astrocytoma, anaplastic oligodendroglioma, and especially glioblastoma, a significant increase in microglia was observed, leading to the formation of dense foci of cellular infiltration (Fig. 12).

Figure 12. Glioblastoma PFZ. Marked microgliosis. H&E, ×400.

PFZ – perifocal zone

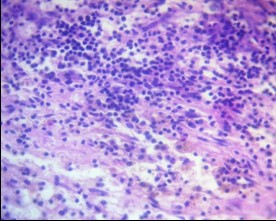

Lymphocytic and leukocyte infiltration

Immune infiltration in the PFZ of glial tumors was a component of the local inflammatory response aimed at limiting tumor invasion, removing necrotic products, and phagocytizing cellular debris. This reaction is considered conditionally protective, although in high-grade gliomas it takes on a dual nature, combining antitumor and immunosuppressive effects. In grades I–II astrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas, lymphocytic infiltration was typically weak, predominantly consisting of perivascular mononuclear cells, without signs of an organized reaction (Fig. 13).

Figure 13. Perivascular lymphoinfiltration zone of oligodendroglioma. H&E, ×400.

In cases of anaplastic astrocytoma, anaplastic oligodendroglioma, and especially glioblastoma, a significant increase in immune cell density was observed: foci of dense lymphocytic infiltration were detected, often with the participation of neutrophils, forming a mixed leukocyte population (Fig. 14). These changes were associated with areas of necrosis, microvascular proliferation, and pronounced perifocal edema, reflecting activation of the innate and adaptive immune response.

Figure 14. Perivascular lymphoinfiltration zone of glioblastoma. Dense lymphocytic/leukocyte infiltration. H&E, ×400.

Zonation of perifocal changes and overall assessment

Based on literature data and research results, perifocal changes in glial tumors were conventionally divided into three zones:

1. Tumor cell invasion zone – characteristic primarily of anaplastic astrocytoma, anaplastic oligodendroglioma, and glioblastoma and manifested by tumor cell penetration into edematous brain tissue, as well as a pronounced vascular reaction in the form of proliferation of endothelial and pericytic elements.

2. Demarcation (boundary) zone – characterized by pronounced edema, destructive changes in astrocytes and oligodendrogliocytes, vascular reaction, lymphocytic and leukocyte infiltration, and the presence of isolated tumor cells.

3. Proliferation zone – characterized by edema and proliferation of glial cells in the absence of tumor cell invasion; considered a zone of predominantly reactive glial remodeling.

The severity of morphological changes was assessed using a three-point system (0–3 points). In all studied variants of glial tumors, the main and most pronounced symptom was edema of the PFZ: the value of this symptom ranged from 2.2(0.2) in oligodendroglioma to 2.9 (0.2) in glioblastoma (Table 1). In astrocytoma and oligodendroglioma, tumor cell invasion into the PFZ was not recorded (0 points). In anaplastic astrocytoma and anaplastic oligodendroglioma, tumor cells in the PFZ were detected in approximately half of the cases (1.5 (0.1) and 1.4 (0.1) points, respectively). In glioblastoma, pronounced invasion was detected in almost all observations (2.9(0.1) points). Astrocytoma and oligodendroglioma were characterized by moderate changes in astrocytes and oligodendrogliocytes (1.5(0.1) and 1.4(0.1) points). In anaplastic astrocytoma this indicator was 1.9(0.2), in anaplastic oligodendroglioma — 1.8(0.2), and the most pronounced changes were noted in glioblastoma (2.7(0.1)) points. In astrocytoma and oligodendroglioma, a moderate vascular reaction was observed (1.2(0.1) and 1.5(0.1) points). Anaplastic variants were characterized by its increase (1.9(0.2), and the maximum vascular reaction was detected in glioblastoma (2.8–2.9(0.1)) points.

The microglial reaction in astrocytoma and oligodendroglioma was moderate (1.5(0.1) and 1.4(0.1) points), in anaplastic forms it reached 1.9(0.1), and in the PFZ of glioblastoma it reached 2.8(0.1) points. Lymphocytic/leukocyte infiltration was moderate in astrocytoma and oligodendroglioma (1.3(0.1)), increased to (2.0–2.2(0.1)) in anaplastic forms and became pronounced in glioblastoma (2.7(0.1)) points. The total score of morphological changes in the PFZ was 7.8–7.9(0.6) for astrocytoma and oligodendroglioma, 11.4–11.5(0.9) for anaplastic variants, and 16.8(0.7) for glioblastoma; the differences between low-grade and anaplastic tumors, as well as between anaplastic forms and glioblastoma, were statistically significant.

|

Table 1. Degrees of morphological changes in the perifocal zone of glial brain tumors (points) |

|||||||

|

Histological Tumor Variants

|

Morphological changes in points (0-3) M(m |

||||||

|

Edema |

Tumor cell invasion |

Changes in astrocytes and oligodermocytes |

Vascular reaction |

Microglial reaction |

Lymphocyte and leukocyte infiltration |

Total |

|

|

Astrocytoma |

2.3(0.2)

|

0 |

1.5(0.1) |

1.2(0.1) |

1.5(0.1) |

1.3(0.1) |

7.9(0.6) |

|

Oligodendroglioma |

2.2(0.2)

|

0 |

1.4(0.1) |

1.5(0.1) |

1.4(0.1) |

1.3(0.1) |

7.8(0.6) |

|

Anaplastic Astrocytoma |

2.5(0.2)

|

1.5(0.1 |

1.9(0.2) |

1.9(0.2) |

1.9(0.1) |

2.0(0.1) |

11.5(0.9)⃰ |

|

Anaplastic Oligodendroglioma |

2.4(0.2) |

1.4 (0.1 |

1.8(0.2) |

1.9(0.2) |

1.9(0.1) |

2.2(0.1) |

11.4(0.9)⃰ |

|

Glioblastoma |

2.9(0.2) |

2.9 (0.1 |

2.7(0.1) |

2.8(0.1) |

2.8(0.1) |

2.7(0.1) |

16.8(0.7)⃰ ⃰⃰⃰ |

|

*Compared with astrocytoma/oligodendroglioma, p<0.05; for glioblastoma, additionally, p<0.01 vs. low-grade tumors and p<0.05 vs. anaplastic tumors. |

|||||||

Discussion

The obtained data confirm that the PFZ in gliomas is not a passive zone of edema, but an active morphofunctional compartment involved in tumor progression. The gradient of morphological changes from astrocytomas and low-grade oligodendrogliomas to anaplastic tumors and glioblastoma reflects a consistent increase in the vasogenic component of edema, microvascular remodeling, and immune infiltration, which is consistent with current concepts of the PFZ/NEPA and the immune microenvironment of gliomas (2, 4–9). Tumor cell invasion into the PFZ in anaplastic gliomas and glioblastomas suggests that the clinically perceived "edema" zone actually includes microscopically infiltrated tissue. This has direct implications for planning the resection volume, assessing residual tumor using the RANO resect criteria, and determining radiation therapy contours (8, 11, 14, 15). The identified angiogenic, inflammatory-reactive, and mixed morphotypes of the PFZ highlight the heterogeneity of perifocal changes and their relationship with the perifocal zone edema (PFO) volume and early functional outcomes. Semiquantitative indices of microvascular density, perivascular space area, and the degree of glial and immune response have demonstrated a relationship with the PFO volume and functional outcomes, allowing them to be considered potential surrogate markers of the severity of the perifocal process and the likelihood of early recurrence (5, 7, 9). Moreover, the morphology of the PFO may vary depending on the tumor's molecular subtype, requiring further studies incorporating an expanded panel of IHC and molecular genetic markers.

Study limitations

The study was conducted at a single center and included a limited number of patients in each histological subgroup, limiting the generalizability of the results. Morphological analysis relied primarily on H&E staining with selective immunohistochemistry and electron microscopic verification; therefore, the molecular features of individual glioma subtypes may not have been fully captured. PFO volume was assessed using T2/FLAIR MRI without standardized inclusion of perfusion and spectroscopic parameters in all patients, which may also impact the accuracy of quantitative comparisons.

Conclusion

The perifocal zone of glial brain tumors is an active morphofunctional compartment in which tumor cell invasion, vasogenic edema, microvascular remodeling, glial reactivity, and immune infiltration sequentially increase with increasing malignancy grade. A semiquantitative PFZ assessment scale based on microvascular density, perivascular space area, and invasion severity can be considered a step toward standardizing the morphological description of the perifocal zone and using its characteristics for stratifying resectability, planning the extent of resection, and personalized anti-edematous and targeted therapy.

Ethics: The study protocol was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the M. Mamakeev National Surgical Center of the Ministry of Health of the Kyrgyz Republic. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2024), ICH GCP, and national requirements. Written informed consent was obtained. Perifocal tissue samples were obtained during standard surgeries without increasing the resection volume; the data were de-identified and anonymized.

Peer-review: External and internal

Conflict of interest: None to declare

Authorship: Z.M.K.

Acknowledgements and Funding: None to declare.

Statement on A.I.-assisted technologies use: Author stated they did not use artificial intelligence (A.I.) tools for writing manuscript.

Data and material availability: Contact authors. Any share should be in frame of fair use with acknowledgement of source and/or collaboration

References

| 1. Konovalov AN, Potapov AA, Yakovlev SB. Immune microenvironment of gliomas and prospects for immunotherapy. Voprosy neurokhirurgii N.N. Burdenko. 2020; 1: 5-14. | ||||

| 2. Reznicenko SV, Kozhevnikov DN, Klimov AE. Morphological and IHC characteristics of the tumor and perifocal zones in glioblastoma. Arch Pathol 2019; 81: 24-30. | ||||

| 3. Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, Brat DJ, Cree IA, Figarella-Branger D, et al. The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the CNS: a summary. Acta Neuropathol 2021; 142: 111-32. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/noab106 PMid:34185076 PMCid:PMC8328013 |

||||

| 4. Diksin M, Konradsson E, Libard S, XXX, XXX, XXX, et al. CD3+, CD8+, and CD20+ infiltration in glioblastoma. Neurooncol Adv 2021; 3: vdaa175. | ||||

| 5. Pinton L, Masetto E, Vettore M, XXX, XXX, XXX, et al. Immune infiltrate in glioblastoma: prognosis & therapy. Front Oncol. 2019; 9: 378. | ||||

| 6. Berghoff AS, Kiesel B, Widhalm G, Rajky O, Ricken G, Wohrer A, et al. Programmed cell death ligand 1 expression and Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol 2015; 17: 1064-75. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nou307 PMid:25355681 PMCid:PMC4490866 |

||||

| 7. Ballestín A, Armocida D, Ribecco V, Seano G. Peritumoral brain zone in GBM. Front Immunol 2024; 15: 1347877 doi:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1347877 https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1347877 PMid:38487525 PMCid:PMC10937439 |

||||

| 8. Scola E, Del Vecchio G, Busto G, Bianchi A, Desideri I, Gadda D, et al. Conventional and advanced magnetic resonance imaging assessment of non-enhancing peritumoral area in brain tumor. Cancers (Basel) 2023; 15: 2992. doi:10.3390/cancers15112992 https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15112992 PMid:37296953 PMCid:PMC10252005 |

||||

| 9. Ohmura K, Tomita H, Hara A. Peritumoral edema in gliomas: mechanisms & management. Biomedicines 2023; 11: 2731. doi:10.3390/biomedicines11102731 https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11102731 PMid:37893105 PMCid:PMC10604286 |

||||

| 10. Gao M, Liu Z, Zang H, Wu X, Yan Y, Lin H, et al. A histopathologic correlation study evaluating glymphatic function in brain tumors by multiparametric MRI. Clin Cancer Res 2024; 30: 4876-86. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-24-0150 PMid:38848042 PMCid:PMC11528195 |

||||

| 11. Karschnia P, Dietrich J, Bruno F, Dono A, Juenger S, Teske N, et al. Surgical management and outcome of newly diagnosed glioblastoma without contrast enhancement (RANO resect report). Neuro Oncol 2024; 26: 166-77. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/noad160 PMid:37665776 PMCid:PMC10768992 |

||||

| 12. Villacis G, Schmidt A, Rudoff JS, Schwenke H, Kuchler J, Schramm P, et al. Evaluating the glymphatic system via magnetic resonance diffusion tensor imaging along the perivascular spaces in brain tumor patients.. Jpn J Radiol 2024; 42: 1146-56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11604-024-01602-7 PMid:38819694 PMCid:PMC11442616 |

||||

| 13. Marin I, Torres F, Riveros R, Oliva B, Vega J, Saavedra C, et al. Evaluation of the DTI ALPS index as a biomarker of glymphatic system at 1.5T. Open Neuroimag J 2025; 18: e18744400389049. https://doi.org/10.2174/0118744400389049250723091323 |

||||

| 14. Roh TH, Kim S-H. Supramaximal resection for glioblastoma: Redefining the extent of resection criteria and its impact on survival. Brain Tumor Res Treat 2023;11: 166-72. https://doi.org/10.14791/btrt.2023.0012 PMid:37550815 PMCid:PMC10409622 |

||||

| 15. Wach J, Vychopen M, Guresir E. Prognostic revalidation of RANO categories for the extent of resection in GBM. J Neurooncol 2025; 172: 515-25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-025-04950-0 PMid:39992571 PMCid:PMC11968501 |

||||

Copyright

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

AUTHOR'S CORNER