Factors of postoperative mortality in stroke-related intracerebral hematoma located in supratentorial region

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE

Factors of postoperative mortality in stroke-related intracerebral hematoma located in supratentorial region

Article Summary

- DOI: 10.24969/hvt.2026.624

- CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASES

- Published: 28/01/2026

- Received: 25/11/2025

- Revised: 15/01/2026

- Accepted: 15/01/2026

- Views: 522

- Downloads: 262

- Keywords: Intracerebral hematoma, hemorrhagic stroke, supratentorial location, postoperative mortality, prognostic factors

Address for Correspondence: Abbasbek Baymatov, National Hospital under the Ministry of Health of the Kyrgyz Republic, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan

E-mail: bai_abbasbek@mail.ru Mobile: +996-555-889-663

ORCID: Mitalip Mamytov - 0009-0008-3968-8224; Abbasbek Baymatov - 0000-0002-2781-0594; Akylbek Akmataliev - 0000-0002-7337-2601

Mitalip Mamytov 1, Abbasbek Baymatov2, Akylbek Akmataliev2

1Kyrgyz State Medical Academy by the name of I.K. Akhunbaev, Department of Neurosurgery of Undergraduate and Postgraduate Education, Bishkek

2National Hospital under the Ministry of Health of the Kyrgyz Republic, Bishkek

Abstract

Objective: Acute cerebrovascular accidents remain a leading cause of mortality and disability. Supratentorial intracerebral hematomas are the most severe form of hemorrhagic stroke, and the effectiveness and optimal timing of their surgical treatment remain a subject of debate.

The aim of the study was to identify independent factors influencing postoperative mortality in the surgical treatment of supratentorial intracerebral hematomas.

Methods: A single-center retrospective cohort study was conducted. Data from 217 patients undergoing surgery for ICH at the National Hospital (2019–2024) were analyzed. Demographic, clinical (time to surgery, level of consciousness according to the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS)), and neuroimaging (volume, location, midline displacement, and severity of intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) according to the Graeb scale) parameters, surgery type, and recurrence were assessed. The primary endpoint was in-hospital mortality. Binary logistic regression analysis (LRA) was used to identify independent predictors of mortality.

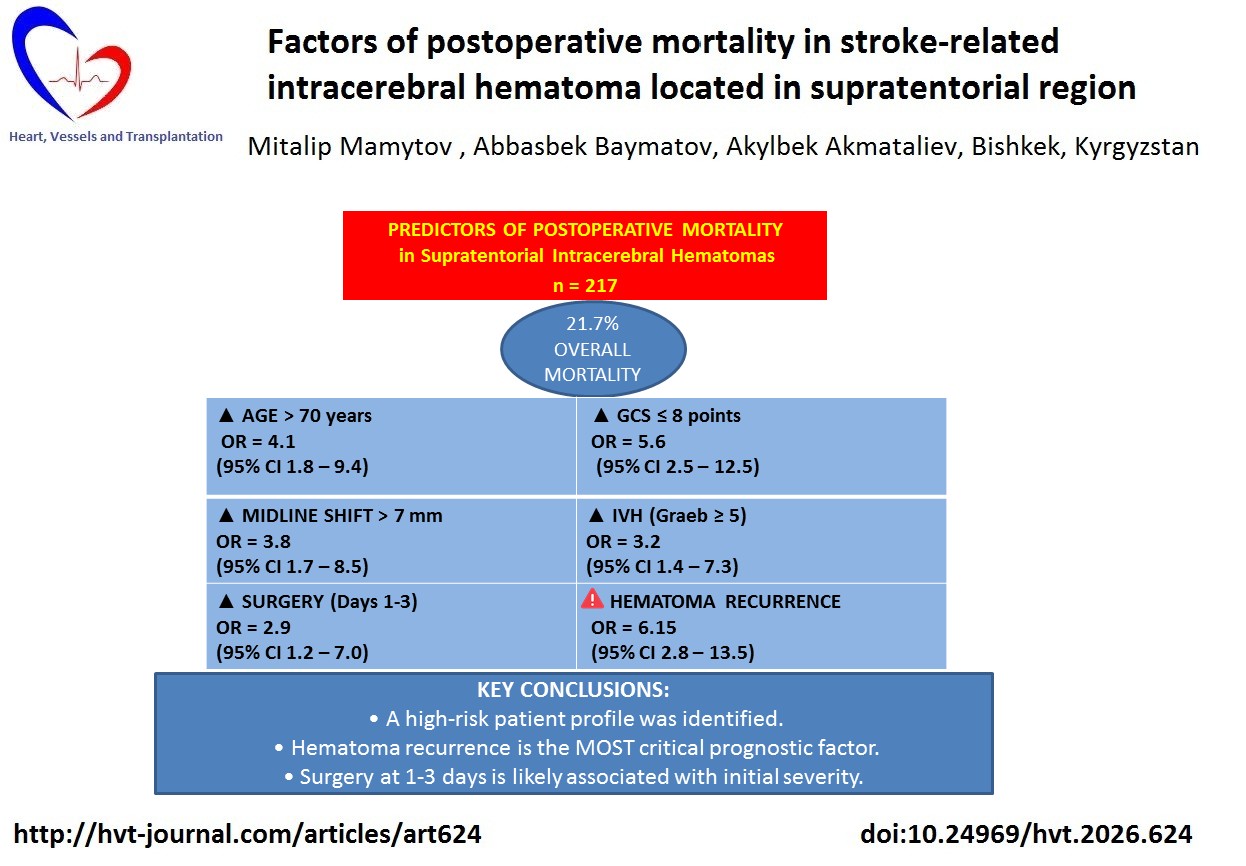

Results: Overall mortality was 21.7% (n=47). Multiple LRA revealed the following independent risk factors for postoperative mortality: age over 70 years (OR=4.1, 95%CI 1.8–9.4; p<0.001), GCS score ≤8 at admission (OR=5.6, 95%CI 2.5–12.5; p<0.001), midline displacement >7 mm (OR=3.8, 95%CI 1.7–8.5; p=0.001), and IVH with Graeb score ≥5 (OR=3.2, 95%CI 1.4–7.3; p=0.006). Surgery performed within 1-3 days from hemorrhage onset was also associated with an increased mortality risk (OR=2.9, 95%CI 1.2-7.0; p=0.018) compared with surgery performed after 10 days. Hematoma recurrence was an extremely unfavorable prognostic factor.

Conclusion: Postoperative mortality after supratentorial intracerebral hematomas is determined by a combination of independent factors: advanced age, profound depression of consciousness, significant brain herniation, and severe intraventricular hemorrhage. Optimization of patient selection for surgical treatment should take these prognostic markers into account. The identified association between higher mortality and surgery performed within 1-3 days requires further study, taking into account the initial severity of the patient's condition.

Key words: Intracerebral hematoma, hemorrhagic stroke, supratentorial location, postoperative mortality, prognostic factors

Graphical abstrac

Introduction

Timely detection and treatment of stroke-related intracerebral hematomas is a pressing medical and social challenge due to their high mortality and disability rates. Despite its smaller share (approximately 15%) in the structure of acute cerebrovascular accidents, hemorrhagic stroke is characterized by the most severe course and the worst prognosis (1). In Kyrgyzstan, the mortality rate from cerebrovascular diseases remains one of the highest among the CIS countries (2- 4).

The development of neurosurgical technologies, including minimally invasive techniques and neuroimaging guidance, has contributed to improved treatment outcomes (7, 8). However, the optimal timing, methods, and criteria for patient selection for surgical intervention for stroke-related supratentorial intracerebral hematomas (SICH) remains controversial, as evidenced by the wide range of postoperative mortality rates (from 0 to 63%) in various studies (9-12).

The aim of the study was to identify independent prognostic factors influencing postoperative mortality in patients with supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage.

Methods

Study design and population

A single-center retrospective cohort study was conducted. The analysis included 217 consecutive patients with SICH who underwent surgery in the neurosurgical departments of the National Hospital of the Ministry of Health of the Kyrgyz Republic between January 2019 and January 2024.

Exclusion criteria: patients with intracerebral hemorrhages due to ruptured arterial aneurysms or arteriovenous malformations; patients with isolated intraventricular hemorrhages without a parenchymal hematoma component.

Patients were divided into 2 groups: survivors (n=170) and died (n=47).

Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the requirement for Ethical approval was waived. Informed consent was obtained from all patients or guardian for all procedures and treatment.

Baseline and clinical characteristics

The following data were collected for each patient: demographic variables: age, sex; clinical: time from onset of hemorrhage symptoms to surgery (categorized as <12 hours, 12-24 hours, 1-3 days, 4-10 days, >10 days), level of consciousness on admission, assessed using the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) (13). For analysis, patients were divided into groups: clear consciousness (15 points), obtundation (11-14), stupor (8-10), and coma I (6-7).

Neuroimaging - computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging

We assessed the following neuroimaging data: hematoma volume, calculated using the formula (A × B × C)/2, hematomas were classified as small (<20 cm³), medium (20-50 cm³), and large (>50 cm³); location - subcortical (lobar), putamenal (lateral), thalamic (medial), mixed; magnitude of midline structure displacement (in mm); and presence and severity of concomitant intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), assessed using the modified Graeb scale (14).

Surgical intervention

Indications for surgery included progressive decline in consciousness, worsening neurological deficits, and signs of dislocation syndrome. The choice of a specific method (open removal, puncture, fibrinolysis) was determined by a multidisciplinary team, taking into account the location and volume of the hematoma, the patient's age, and comorbidities. The following surgical variables were included in analysis: type of surgical intervention performed (osteoplasty craniotomy, decompressive craniotomy, puncture removal, local fibrinolysis).

Follow-up and outcomes

We included in analysis in hospital during postoperative period follow-up data. The following outcomes were recorded: in-hospital mortality and development of hematoma recurrence in the postoperative period.

Statistical analysis

Statistical processing of the data was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.0. Quantitative data not normally distributed (tested with the Shapiro-Wilk test) are presented as medians and interquartile ranges (M (Q25-Q75)) and compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables are presented as absolute and relative frequencies (n, %) and compared using the Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. To identify independent factors associated with postoperative mortality, we used binary logistic regression (the enter-method). Variables that demonstrated a statistically significant association (p < 0.1) with mortality in univariate analysis were included in the model. Multiple logistic regression analysis results are presented as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Clinical characteristics

Of the 217 patients included in the study, 47 (21.7%) died. The mean patient age was 56.9 (47.0; 68.0) years. There were 129 men (59.4%). The distribution of patients by clinical and neuroimaging characteristics by outcome is presented in Table 1.

The patients who died were of older age (p<0.001), they had markedly lower Glasgow coma grade score on admission (p<0.001), more patients who underwent surgery with 1-3 days died (p=0.003), they had tendency to higher hematoma volume, and significantly higher number of patients with mixed type by hematoma location (p=0.017) and larger midline displacement died (p<0.001) and they had higher Graeb score, i.e. severe IVH and hematoma recurrence (p<0.001 for both) as compared to survivors (Table 1).

|

Table 1. Comparison of clinical and neuroimaging characteristics between the groups of surviving and deceased patients |

||||

|

Variables |

All patients (n=217) |

Survived (n=170) |

Died (n=47) |

p |

|

Age, years, Me (Q25–Q75) |

56.9 (47.0; 68.0) |

54.5 (45.0; 65.0) |

68.0 (60.0; 75.0) |

<0.001 |

|

Age >70 years, n (%) |

52 (24.0) |

32 (18.8) |

20 (42.6) |

0.001 |

|

GCS at admission, n (%) |

<0.001 |

|||

|

- Fully conscious (GCS 15) |

18 (8.3) |

17 (10.0) |

1 (2.1) |

|

|

- Drowsy / obtunded (GCS 11–14) |

89 (41.0) |

82 (48.2) |

7 (14.9) |

|

|

- Stuporous (GCS 8–10) |

59 (27.2) |

39 (22.9) |

20 (42.6) |

|

|

- Coma (grade I) (GCS 6–7) |

51 (23.5) |

32 (18.8) |

19 (40.4) |

|

|

GCS ≤8, n (%) |

110 (50.7) |

71 (41.8) |

39 (83.0) |

<0.001 |

|

Continued on page XXX |

||||

|

Table 1. Comparison of clinical and neuroimaging characteristics between the groups of surviving and deceased patients Continued from page XXX |

||||

|

Variables |

All patients (n=217) |

Survived (n=170) |

Died (n=47) |

p |

|

Time to surgery, n (%) |

0.003 |

|||

|

─ <12 hours |

8 (3.7) |

6 (3.5) |

2 (4.3) |

|

|

─ 12–24 hours |

9 (4.1) |

7 (4.1) |

2 (4.3) |

|

|

─ 1–3 days |

76 (35.0) |

53 (31.2) |

23 (48.9) |

|

|

─ 4–10 days |

77 (35.5) |

59 (34.7) |

18 (38.3) |

|

|

─ >10 days |

47 (21.7) |

45 (26.5) |

2 (4.3) |

|

|

Hematoma volume, n (%) |

0.052 |

|||

|

─ Small (<20 cm³) |

20 (9.2) |

14 (8.2) |

6 (12.8) |

|

|

─ Medium (20–50 cm³) |

96 (44.2) |

80 (47.1) |

16 (34.0) |

|

|

─ Large (>50 cm³) |

101 (46.5) |

76 (44.7) |

25 (53.2) |

|

|

Location, n (%) |

0.017 |

|||

|

─ Subcortical |

62 (28.6) |

55 (32.4) |

7 (14.9) |

|

|

─ Putamenal |

74 (34.1) |

55 (32.4) |

19 (40.4) |

|

|

─ Thalamic |

37 (17.1) |

31 (18.2) |

6 (12.8) |

|

|

─ Mixed |

44 (20.3) |

29 (17.1) |

15 (31.9) |

|

|

Midline structure displacement, n (%) |

<0.001 |

|||

|

─ Absent |

29 (13.4) |

26 (15.3) |

3 (6.4) |

|

|

─ 1–3 mm |

62 (28.6) |

51 (30.0) |

11 (23.4) |

|

|

─ 4–7 mm |

71 (32.7) |

56 (32.9) |

15 (31.9) |

|

|

─ >7 mm |

55 (25.3) |

37 (21.8) |

18 (38.3) |

|

|

IVH (Graeb scale), n (%) |

<0.001 |

|||

|

─ None / 1–2 points |

146 (67.3) |

126 (74.1) |

20 (42.6) |

|

|

─ 3–6 points |

65 (30.0) |

41 (24.1) |

24 (51.1) |

|

|

─ ≥7 points |

6 (2.8) |

3 (1.8) |

3 (6.4) |

|

|

IVH (Graeb) ≥5, n (%) |

31 (14.3) |

17 (10.0) |

14 (29.8) |

<0.001 |

|

Hematoma recurrence, n (%) |

18 (8.3) |

8 (4.7) |

10 (21.3) |

<0.001 |

|

Data are presented as median (Q25-Q75) and number percentage Mann-Whitney U test, Chi-square or Fischer exact tests GCS - Glasgow Coma Scale, IVH – intraventricular hemorrhage |

||||

Predictors of mortality

The results of binary logistic regression to identify independent predictors of postoperative mortality are presented in Table 2.

The analysis showed that advanced age (p<0.001), severe impairment of consciousness (p<0.001), marked brain displacement (p<0.001), severe IVH (p=0.006), and the development of hematoma recurrence (p<0.001) were independent factors significantly increasing the risk of mortality. Surgical intervention performed within 1–3 days from the onset of hemorrhage was also associated with a higher risk of mortality compared with interventions performed after 10 days (p=0.018).

|

Table 2. Independent factors associated with postoperative mortality (multiple logistic regression analysis) |

|||

|

Predictor |

OR |

95% CI |

p |

|

Age >70 years |

4.10 |

1.81 – 9.39 |

<0.001 |

|

GCS on admission ≤8 points |

5.62 |

2.52 – 12.54 |

<0.001 |

|

Surgery within 1–3 days (ref.: >10 days) |

2.90 |

1.20 – 7.03 |

0.018 |

|

Displacement of midline structures >7 mm |

3.81 |

1.71 – 8.51 |

0.001 |

|

IVF (Graeb scale) ≥5 points |

3.21 |

1.40 – 7.34 |

0.006 |

|

Hematoma recurrence |

6.15 |

2.15 – 17.60 |

<0.001 |

|

CI – confidence interval, GCS - Glasgow Coma Scale, IVH – intraventricular hemorrhage, OR - odds ratio |

|||

Discussion

The results of our study allowed us to identify a set of independent factors determining the risk of postoperative mortality in patients with SICH. These factors include age over 70 years, a GCS score ≤8, midline shift greater than 7 mm, and severe IVH (Graeb score ≥5).

Our findings are consistent with previously published studies demonstrating the negative impact of advanced age, decreased level of consciousness, and mass effect on surgical outcomes (11). Severe IVH is well known to significantly worsen prognosis due to the development of obstructive hydrocephalus and toxic injury to brain tissue caused by blood breakdown products (5, 6).

Of particular interest is the observed association between surgery performed within 1–3 days and increased mortality. This finding likely reflects not the detrimental effect of early intervention itself, but rather the initial severity of patients’ conditions at the time of surgery. In our cohort, the majority of patients (62.7%) were admitted to the neurosurgical department from other hospitals after neuroimaging had been performed, which introduced a selection bias: patients operated on early were those in the most severe condition, with rapid neurological deterioration and brain displacement, whereas more stable patients could undergo delayed surgery. This observation highlights the importance of accounting for baseline disease severity when comparing surgical timing and underscores the need for prospective randomized studies to determine the optimal timing of intervention (9).

Hematoma recurrence proved to be an extremely unfavorable prognostic factor, demonstrating the highest odds ratio (OR 6.15), which is consistent with literature data reporting high mortality rates in cases of recurrent hemorrhage. This finding emphasizes the critical importance of meticulous intraoperative hemostasis and strict postoperative blood pressure control.

Study limitations

This study has several limitations, including its retrospective design and single-center nature, which may limit the generalizability of the results. The presence of selection bias related to the timing of hospitalization and surgery may have influenced the analysis of the time-to-surgery factor. Long-term functional outcomes (e.g., modified Rankin Scale scores) were not assessed, which limits the evaluation of quality of survival.

Strengths

The strengths of this study include a relatively large and homogeneous patient cohort, a detailed analysis of clinical and neuroimaging parameters, and the use of multivariate statistical analysis to identify independent predictors of mortality.

Conclusions

Postoperative mortality following surgical treatment of supratentorial intracerebral hematomas is determined by a set of independent factors, including advanced age (>70 years), severe impairment of consciousness (GCS ≤8), pronounced midline shift (>7 mm), and severe concomitant intraventricular hemorrhage (Graeb score ≥5). Hematoma recurrence is an extremely unfavorable prognostic factor that markedly increases the risk of death.

The association between surgery performed within 1–3 days and increased mortality is likely mediated by the initial severity of patients’ conditions and requires further investigation in prospective studies.

Consideration of the identified prognostic factors may help optimize patient selection for surgical treatment and improve clinical outcomes.

Ethics: Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the requirement for Ethical approval was waived. Informed consent was obtained from all patients or guardian for all procedures and treatment

Peer-review: External and internal

Conflict of interest: None to declare

Authorship: M.M., A.B. and A.A equally contributed to the study and preparation of manuscript, thus filled all authorship criteria

Acknowledgements and Funding: None to declare.

Statement on A.I.-assisted technologies use: Author stated they did not use artificial intelligence (A.I.) tools for writing manuscript

Data and material availability: Contact authors. Any share should be in frame of fair use with acknowledgement of source and/or collaboration

References

| 1.Parker D Jr, Rhoney DH, Liu-DeRyke X. Management of spontaneous nontraumatic intracranial hemorrhage. J Pharm Pract 2010; 23: 398-407. https://doi.org/10.1177/0897190010372320 PMid:21507845 |

||||

| 2.Yrysova MB, Yrysov KB, Toychibaeva RI, Ablabekova MM. Assessment of trends in morbidity and mortality from stroke in the Kyrgyz Republic. Zdrav Kyrgyzstana 2024; 2: 133-9. . doi:10.51350/zdravkg2024.2.6.19.133.139 https://doi.org/10.51350/zdravkg2024.2.6.19.133.139 |

||||

| 3.Health Policy Analysis Center. Events (Internet). Bishkek; 2024 (cited 2025 Jan 15). Available from: URL: http://hpac.kg/ru/category/события/ | ||||

| 4.World Life Expectancy. Stroke in Kyrgyzstan (Internet). 2024 (cited 2025 Jan 15). Available from: URL: https://www.worldlifeexpectancy.com/kyrgyzstan-stroke | ||||

| 5.Eslami V, Tahsili-Fahadan P, Rivera-Lara L, Gandhi D, Ali H, Perry-Jones A, et al. Influence of intracerebral hemorrhage location on outcomes in patients with severe intraventricular hemorrhage. Stroke. 2019; 50: 1688-95. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.024187 PMid:31177984 PMCid:PMC6771028 |

||||

| 6.Stein M, Luechke M, Preuss M, Boeker DK, Joedicke A, Oertel MF. Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage with ventricular extension and grading of obstructive hydrocephalus: prediction of outcome of a life-threatening entity. Neurosurgery 2010; 67: 1243-52. https://doi.org/10.1227/NEU.0b013e3181ef25de PMid:20948399 |

||||

| 7.Kuo LT, Chen CM, Li CH, Tsai JC, Chiu HC, Liu LC, et al. Early endoscope-assisted hematoma evacuation in patients with supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage: case selection, surgical technique, and long-term results. Neurosurg Focus 2011; 30: E9. https://doi.org/10.3171/2011.2.FOCUS10313 PMid:21456936 |

||||

| 8.Nagasaka T, Tsugeno M, Ikeda H, Okamoto T, Inao S, Wakabayashi T. Early recovery and better evacuation rate in neuroendoscopic surgery for spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage using a multifunctional cannula: preliminary study compared with craniotomy. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2011; 20: 208-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2009.11.021 PMid:20621516 |

||||

| 9.Cai Q, Zhang H, Zhao D, Yang Z, Hu K, Wang L, et al. Analysis of three surgical treatments for spontaneous supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017; 96: e8435. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000008435 PMid:29069046 PMCid:PMC5671879 |

||||

| 10.Katsuki M, Kakizawa Y, Nishikawa A, Yamamoto Y, Uchikawa T. Endoscopic hematoma removal of supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage under local anesthesia reduces operative time compared to craniotomy. Sci Rep 2020; 10: 10389. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67456-x PMid:32587368 PMCid:PMC7316752 |

||||

| 11.Akpinar E, Gurbuz MS, Berkman MZ. Factors affecting prognosis in patients with spontaneous supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage under medical and surgical treatment. J Craniofac Surg 2019; 30: e667-71. https://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0000000000005733 PMid:31306386 |

||||

| 12.Chen F, Chen T, Nakaji P. Adjustment of the endoscopic third ventriculostomy entry point based on the anatomical relationship between coronal and sagittal sutures. J Neurosurg 2013; 118: 510-3. https://doi.org/10.3171/2012.11.JNS12477 PMid:23259823 |

||||

| 13. Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness . A practical scale. Lancet 1974; 13: 81-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(74)91639-0 PMid:4136544 |

||||

| 14. Morgan TC, Barber PA, Hill MD, Silver FL, Demchuk AM, Buchan AM. The modified Graeb score: an enhanced tool for intraventricular hemorrhage measurement and prediction of functional outcome. Stroke 2013; 44: 635-41.. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.670653. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.670653 PMid:23370203 PMCid:PMC6800016 |

||||

Copyright

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

AUTHOR'S CORNER