The evaluation of cTnT/CK-MB ratio is as a predictor of change in cardiac function after myocardial infarction

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE

The evaluation of cTnT/CK-MB ratio is as a predictor of change in cardiac function after myocardial infarction

Article Summary

- DOI: 10.24969/hvt.2021.269

- Page(s): 113-122

- CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASES

- Published: 09/09/2021

- Received: 11/07/2021

- Revised: 04/09/2021

- Accepted: 04/09/2021

- Views: 11165

- Downloads: 5885

- Keywords: Cardiac troponin T (cTnT), creatine kinase (CK)-MB, left ventricular remodeling, acute myocardial infarction, cardiovascular magnetic resonance

Address for correspondence: Ferhat Eyyupkoca, Department of Cardiology, Sincan State Hospital, Metropol Str, 06940 Sincan, Ankara, Turkey Ankara, Turkey

Mobile: +9055056864352 E-mail: eyupkocaferhat@gmail.com

Ferhat Eyyupkoca1, Ercan Karabekir2, Emrullah Kiziltunc3, Cengiz Sabanoglu4, Mehmet Sait Altintas5, Onur Yildirim6, Ajar Kocak1, Gultekin Karakus7, Mehmet Ali Felekoglu8, Can Ozkan9

1Department of Cardiology, Nafiz Korez Sincan State Hospital, Ankara, Turkey

2Department of Radiology, Ankara Bilkent City Hospital, Ankara, Turkey

3Department of Cardiology, Gazi University Medical School, Ankara, Turkey

4Department of Cardiology, Kirikkale State Hospital, Kirikkale, Turkey

5Department of Cardiology, Istanbul Yedikule Training and Research Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey

6Department of Cardiology, Lokman Hekim University Medical School, Ankara, Turkey

7Department of Cardiology, Acibadem Mehmet Ali Aydinlar Universtity Medical School, Turkey

8Department of Cardiology, Atakent Hospital, Yalova, Turkey

9Department of Cardiology, Mus State Hospital, Mus, Turkey

Abstract

Objective: Cardiac enzymes that are released during acute myocardial infarction (AMI) are of prognostic importance. This study aimed to investigate the relationship between cardiac troponin T (cTnT) and creatine kinase myocardial band (CK-MB) release during AMI and 6-month post-AMI left ventricular (LV) function, as assessed by magnetic resonance imaging.

Methods: This prospective cohort observational study included 131 adult patients (113 males, 18 females, mean age 53.8 (8.6) years) who had been diagnosed with a new ST-segment elevation AMI (STEMI) in the emergency department. Cardiac enzymes were assessed by serial measurements. Blood samples obtained at 12 h post-AMI were included in the analysis. The reference value for CK-MB was 2–25 U/L, while for troponin it was - 0.1 ng/mL. Values above the reference limit were accepted as positive. Patients underwent cardiovascular magnetic resonance at 2 weeks and 6 months post-AMI. LV stroke volume was quantified as LV EDV – LV ESV, and ejection fraction (EF) was determined with the following equation: EF = [(LV EDV – LV ESV)/LV EDV] × 100. Adverse remodeling was defined based on the threshold values that are commonly accepted for changes in the LV end-diastolic volume (∆LV-EDV, >10%) and LV end-systolic volume (∆LV-ESV, >12%).

Results: All of the patients were cTnT- and CK-MB-positive at 12 h. There was no found significant difference between both groups regarding the risk factors of coronary artery disease (including diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia and smoking). Adverse cardiac remodeling was observed in 32.1% (n = 42) of the patients. cTnT/CK-MB was determined to be an independent predictor of the ΔLV-EDV (β ( SE = 0.55 ( 0.08, p<0.001), ΔLV-ESV (β ( SE = 1.12 ( 0.28, p<0.001), and adverse remodeling (OR = 1.13, p<0.001). The cTnT/CK-MB ratio was able to predict adverse remodeling with 85.7% sensitivity and 74.2% specificity (area under the ROC curve (AUC) = 0.856, p<0.001). The cTnT levels were able to predict adverse remodeling with 73.8% sensitivity and 78.7% specificity (AUC = 0.796, p<0.001). CK-MB did not significantly predict adverse remodeling (AUC = 0.516, (p=0.758).

Conclusion: The cTnT/CK-MB ratio was superior to its components in predicting changes in LV function after STEMI. The cTnT/CK-MB ratio can be used in clinical practice for risk stratification and treatment optimization.

Key words: Cardiac troponin T (cTnT), creatine kinase (CK)-MB, left ventricular remodeling, acute myocardial infarction, cardiovascular magnetic resonance

Introduction

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) causes functional and structural changes in the heart through complex mechanisms such as cell death, cytokine storm, and increased collagen production (1, 2). Cardiac enzymes are important diagnostic markers for myocardial damage (3). When the ischemic injury becomes irreversible, the intracellular acidosis and proteolytic enzyme activation cause the disintegration of the contractile apparatus and the release of high concentrations of cardiac troponin T (cTnT) and creatine kinase myocardial band (CK-MB) (4). The comparatively early clearance of CK-MB from circulation aids in the detection of re-infarction. For this reason, it has been recommended in the literature to evaluate cTnT and CK-MB fraction in the setting of AMI (5).

The resulting cardiac remodeling is an important predictor of heart failure and mortality (6-8). Cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging is the gold standard for determining myocardial function, myocardial mass, and scarring, and is increasingly used to assess cardiac remodeling (9). It is known that advanced radiological imaging is often not possible due to its high cost, patient noncompliance, and advanced renal dysfunction. Hence, simpler, cost-effective, easier, and more accessible methods are needed to predict left ventricular (LV) remodeling after AMI.

The and CK-MB have both been associated with post-AMI cardiac injury, scar size, and adverse remodeling; however, it is unclear whether one is superior to the other (10, 11). Moreover, no studies could be found in the literature concerning the relationship between the cTnT/CK-MB ratio, and cardiac parameters and adverse remodeling after AMI.

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between the cTnT, CK-MB, and cTnT/CK-MB, and cardiac function assessed by CMR, and their superiority over each other in prediction of left ventricular (LV) remodeling in AMI patients.

Methods

The study was designed in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki (as revised in Brazil, 2013) and Good Clinical Practice Guidelines. The study was granted approval by the local ethics committee. (Registration number: 26/06/13-106) All of the participants signed informed consent forms.

Study design population

The prospective cross-sectional study included 131 patients (>18 and <70 years of age) who were admitted to the hospital with ST-segment elevation AMI (STEMI) for the first time and underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) within 12 h after the onset of chest pain. STEMI was defined according to the fourth universal definition of AMI and managed according to the latest European Society of Cardiology guidelines (12, 13).

The exclusion criteria were as follows: cardiogenic shock, right ventricular infarction, unsuccessful reperfusion (Thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) score<III), any complication during PCI or requiring re-PCI during follow-up, any coronary lesion planned for elective PCI after angiography, re-infarction, history of silent ischemia/infarction, any systemic inflammatory disease, autoimmune diseases, chronic renal failure, chronic hemodialysis, trauma or skeletal muscle injury during the last week, scheduled emergency or elective coronary artery bypass graft surgery after angiography. The patients who needed thrombus aspiration or glycoprotein IIb-IIIa inhibitors infusion were also excluded from study.

Angiographic Procedure

The femoral or radial approach was used for coronary angiography and primary PCI. All patients received drug-eluting stents. TIMI III flow was achieved in all patients. All patients received medical treatment according to 2017 ESC guideline on acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-Segment elevation guidelines (13).

Biochemical parameters

Serial blood samples were taken (2–12 h) for biochemical analysis. The time dependent diagnostic performance of conventional cardiac markers for detection of massive acute and subacute myocardial infarction and minimal myocardial damage can change rapidly (14). It is shown that Up to 4 to 8 h after onset of symptoms the sensitivity of cTnT ELISA is about 92%; whereas from 12 h onwards the sensitivities of cTnT ELISA are close to 100%. CK-MB is initially most sensitive up to 8-12h (15). So, in this study, 12h cTnT/CK-MB ratio was determined as time course for the highest efficacy of the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity. Blood samples obtained at 12 h post-AMI were included in the analysis. Peripheral venous blood samples were taken from all of the patients and used for the complete blood count, blood biochemistry, and cardiac biomarker assessment. Hematological parameters were determined using a Horiba Pentra DX120 automated hematology analyzer (Montpellier, France), while for the biochemical parameters, a Roche Cobas C501 autoanalyzer (Basel, Switzerland) was used.

The CK-MB and cTnT levels were studied using the Roche Diagnostics Elecsys 2010 immunoassay analyzer and the reagents purchased from the same company.

The reference values were 2–25 U/L and 0.1 ng/mL for CK-MB and cTnT respectively. Values above the reference limit were accepted as positive. All the patients had positive cTnT- and CK-MB values 12h post AMI.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging

Patients underwent CMR at 2 weeks and 6 months post-AMI. All of the CMR examinations were performed using a Magnetom Skyra 3-T scanner (Siemens Medical Systems, Erlangen, Germany). The CMR imaging protocol included one four-chamber view, cine short-axis sections (slice thickness 6 mm at 10-mm intervals), and one two-chamber view. The indices of the LV systolic function were evaluated with retrospective electrocardiogram-gated turbo-fast low angle shot (turbo-FLASH) sequence. Imaging parameters were as follows: echo time of 1.42 ms, repetition time of 39 ms, flip angle of 57°, and voxel size of 1.67 × 1.67 × 6 mm. The CMR images were transferred to a workstation. The LV end-diastolic volume (LV-EDV) and LV end-systolic volume (LV-ESV) were measured using Siemens syngo.via VA30 imaging software (Erlangen, Germany). The papillary muscles were excluded and the endocardial borders of end-diastolic and end-systolic phases of the short-axis stack images, which covered the LV from the mitral annular line to the apex, were manually traced. The end-diastolic phase was selected as the first phase of the cine images. The end-systolic phase was determined visually by identifying the end of the inward movement of the LV wall (16).

Adverse remodeling was defined based on the threshold values that are commonly accepted for changes in the ∆LV-EDV (>10%) and ∆LV-ESV (>12%) (17). LV stroke volume was quantified as LV EDV – LV ESV, and ejection fraction (EF) was determined with the following equation: EF = [(LV EDV – LV ESV)/LV EDV] × 100. Reverse remodeling was defined as an improvement in cardiac function and dimensions at six months follow up.

Statistical analysis

Statistical evaluation was performed using STATA (Stata Corp LLC, TX, USA) software. The normal distribution of the numerical data was evaluated using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Normally distributed variables were presented as the mean (standard deviation, while non-normally distributed variables were presented as the median (minimum-maximum). Categorical variables were expressed as numbers and percentages. The student t and Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare the numerical variables between patients with reverse and adverse cardiac remodeling. The Chi-square and Fisher exact Chi- square tests were used for comparison of the categorical data. In all patients, changes in the CMR findings were evaluated using the paired sample t test or Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Any correlations between the numerical variables were analyzed using Spearman correlation analysis. It was evaluated by mixed model analysis in repeated measures to identify predictors of changes in LV EDV and LV ESV at 6-month follow-up (dependent variables; ΔLV EDV and ΔLV ESV, respectively). Variables that correlated with ΔLV EDV and ΔLV ESV from demographic and laboratory findings were included in the multivariable regression model. Logistic regression analysis was used to determine independent parameters for adverse remodeling, another important dependent variable. Demographic and laboratory findings that differed between the reverse remodeling and reverse remodeling groups were included in the multivariable logistic regression model. The effects of demographic characteristics consistent with traditional risk factors (age, sex, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, family history, and smoking status) were adjusted in both regression models (18, 19). Systolic and diastolic blood pressure, door-to- balloon time, symptom-to-balloon time, laboratory parameters, and cardiac output and cardiac index in CMR were evaluated as potential risk factors for adverse remodeling, ΔLV EDV and ΔLV ESV. Diagnostic value of cardiac markers was evaluated with area under the curve (AUC) value, 95% confidence interval (CI), sensitivity, specificity, negative predictive value (NPV) and positive predictive value (PPV) using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. The optimal cut-off point was determined using the Youden index. A p<0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

The study included 131 patients (113 males, 18 females, mean age 53.8 (8.6) years) who had been diagnosed with STEMI for the first time. Among the patients, 32.1% (n = 42) had hypertension, 33.6% (n = 44) had diabetes mellitus, and 44.3% (n = 58) had hyperlipidemia. Moreover, 64.1% (n = 84) of the patients were smokers or had a history of smoking. The mean door-to-balloon time was 46.2(11.3) minutes. At the time of the AMI, the median cTnT level was 1.4 (range of 0.3–30.0), the median CK-MB level was 47 (range of 26–496), and the median cTnT/CK-MB ratio was 2% (range of 0.1%–89%). Demographic information and laboratory results are presented in detail in Table 1.

|

Table 1. Demographic and laboratory findings of the patients |

|

|

Variables |

All population n=131 |

|

Demographic findings |

|

|

Gender, n(%) |

|

|

Female |

18(13.7) |

|

Male |

113(86.3) |

|

Age, years |

53.8(8.6 |

|

BMI, kg/m2 |

27.3(7.5 |

|

Hypertension, n(%) |

42(32.1) |

|

Diabetes mellitus, n(%) |

44(33.6) |

|

Hyperlipidemia, n(%) |

58(44.3) |

|

Family history, n(%) |

|

|

Current or former smoking, n(%) |

84(64.1) |

|

Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg |

123(19.9 |

|

Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg |

75.6(13.3 |

|

Door-to-balloon time, min |

46.2(11.3) |

|

Symptom-to-balloon time, min |

342.3(83.8) |

|

Laboratory findings |

|

|

hs-cTnT, ng/ml |

1.4(0.3-30.0) |

|

CK-MB, U/L |

47(26-496) |

|

cTnT/CK-MB ratio, % |

2(0.1-89.0) |

|

Hemoglobin, g/dL |

14.2(1.6) |

|

Platelet, x103 µL |

237.9(63.1) |

|

LDL, mg/dL |

136(40.9) |

|

HDL, mg/dL |

38.9(8.4) |

|

Creatinine, mg/dL |

1.0(0.2) |

|

Albumin, g/dL |

4.2(1.5) |

|

hs-CRP, µg/L |

17.0(1.0-139.0) |

|

Numerical variables are shown as the mean (standard deviation) or median (min-max). Categorical variables are shown as numbers (%). BMI - body mass index, hs-cTnT - high sensitive cardiac troponin T, CK-MB - creatine kinase MB, LDL - low density lipoprotein, HDL - high density lipoprotein, hs-CRP - high sensitive C-reactive protein |

|

When compared to the baseline CMR findings, the mean EF (48.1 (9.1) vs. 51.0 (9.2), p<0.001) and mean LV-ESV (68.2 (16.2) vs. 70.0 (16.3), p=0.015) increased, while the median LV-ESV decreased (73.8 vs. 67, p=0.015). The other CMR findings were not significantly different (Table 2). Adverse cardiac remodeling was observed in 32.1% (n=42) of the patients.

The increase in the ΔLV-EDV was more prominent in the female patients (6% vs. 1%, p = 0.036), whereas the ΔLV-ESV was not statistically different for the two genders (5% vs. 4%, P = 0.779). The ΔLV-EDV and ΔLV-ESV were not significantly associated with comorbidities.

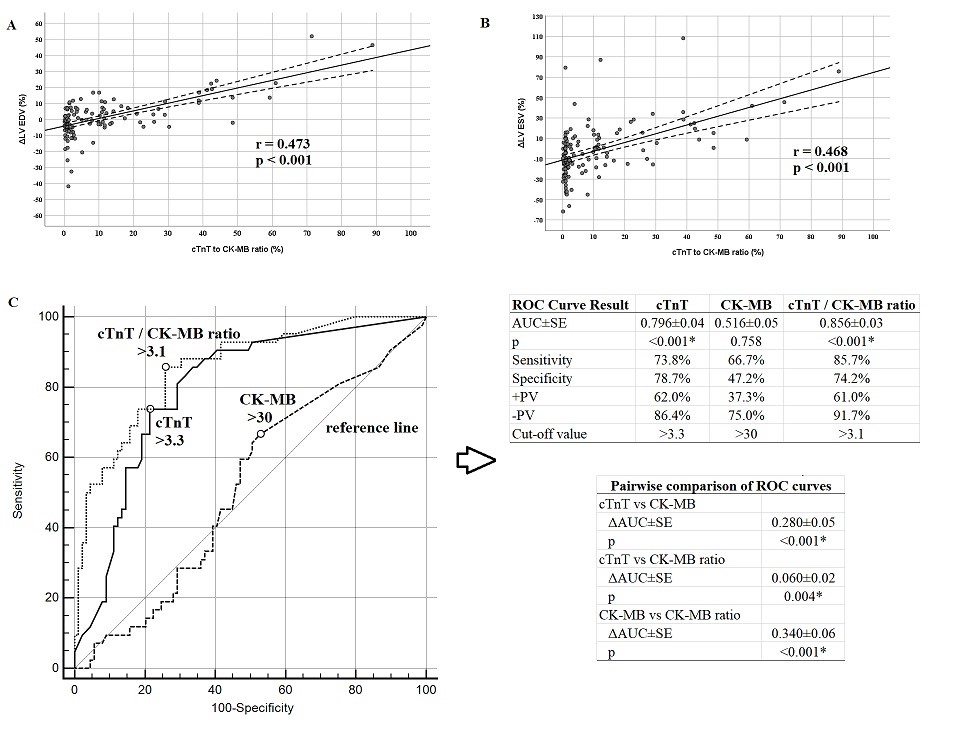

The cTnT/CK-MB ratio was positively correlated with the ΔLV-EDV (r=0.473, p<0.001; Fig. 1A) and ΔLV-ESV (r = 0.468, p<0.001; Fig. 1B). The ΔLV-EDV was not significantly correlated with other laboratory findings. The low-density lipoprotein (LDL) level was positively correlated with the ΔLV-ESV (r = 0.260, p = 0.012) and cTnT/CK-MB ratio (r = 0.290, p = 0.005) (Table 3).

The median cTnT (15 vs. 0.4, p<0.001) and cTnT/CK-MB ratios (16 vs. 1, p<0.001) were significantly higher in the adverse remodeling group. The adverse and reverse remodeling groups were similar in terms of the demographic characteristics and other laboratory findings (Table 4).

In the regression model that included the traditional and potential risk factors, cTnT/CK-MB was an independent predictor of the ΔLV-EDV (β (SE) = 0.55 (0.08), p<0.001), ΔLV-ESV (β (SE)=1.12 (0.28), p<0.001), and adverse remodeling (OR=1.13, p< 0.001) (Table 5).

|

Table 2. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance findings |

|||

|

CMR findings |

Baseline n=131 |

6th months n=131 |

p |

|

LV EF, % |

48.1(9.1) |

51.0(9.2) |

<0.001* |

|

LV EDV, mL |

149.3(32.4) |

148.4(31.3) |

0.544 |

|

LV ESV, mL |

73.8(30-180) |

67(29-153) |

0.010* |

|

Stroke volume, mL |

70.0(16.3) |

68.2(16.2) |

0.015* |

|

Cardiac output, L/min |

4.8(1.0) |

5.0(1.1) |

0.224 |

|

Cardiac index, L/min/m2 |

2.5(0.5) |

2.6(0.5) |

0.235 |

|

Numerical variables are shown as the mean ( standard deviation or median (min-max) EF – ejection fraction, *p < 0.05 is statistically significant. CMR - cardiovascular magnetic resonance, LV - left ventricular, EF - ejection fraction, EDV - end-diastolic volume index, ESV - left ventricular end-systolic volume |

|||

|

Table 3. Relationship between the clinical parameters and the LV EDV, LV ESV, and cTnT/CK-MB ratio |

||||||

|

Variables |

ΔLV EDV n=131 |

ΔLV ESV n=131 |

cTnT/CK-MB ratio n=131 |

|||

|

r |

p |

r |

p |

r |

p |

|

|

Age |

0.052 |

0.556 |

0.001 |

0.992 |

0.015 |

0.865 |

|

BMI |

-0.107 |

0.225 |

-0.157 |

0.073 |

-0.012 |

0.892 |

|

Systolic blood pressure |

0.170 |

0.092 |

0.316 |

0.001* |

0.140 |

0.167 |

|

Diastolic blood pressure |

0.133 |

0.188 |

0.219 |

0.030* |

0.060 |

0.557 |

|

Door to balloon time |

0.218 |

0.903 |

0.207 |

0.712 |

0.263 |

0.255 |

|

Symptom to balloon time |

0.244 |

0.880 |

0.279 |

0.650 |

0.285 |

0.166 |

|

cTnT |

0.362 |

0.002* |

0.370 |

<0.001* |

0.750 |

<0.001* |

|

CK-MB |

0.298 |

0.023* |

0.286 |

0.045* |

0.340 |

0.001* |

|

cTnT/CK-MB ratio |

0.473 |

<0.001* |

0.468 |

<0.001* |

- |

- |

|

Hemoglobin |

-0.055 |

0.603 |

0.127 |

0.227 |

-0.051 |

0.629 |

|

Platelet |

0.093 |

0.376 |

-0.121 |

0.250 |

-0.061 |

0.564 |

|

LDL |

-0.167 |

0.109 |

0.260 |

0.012* |

0.290 |

0.005* |

|

HDL |

-0.034 |

0.752 |

-0.060 |

0.574 |

-0.088 |

0.408 |

|

Creatinine |

0.011 |

0.918 |

0.030 |

0.766 |

-0.046 |

0.654 |

|

Albumin |

-0.250 |

0.333 |

-0.218 |

0.400 |

0.005 |

0.985 |

|

hs-CRP |

-0.011 |

0.959 |

0.135 |

0.539 |

-0.266 |

0.220 |

|

ΔLV EF |

-0.358 |

<0.001* |

-0.451 |

<0.001* |

-0.326 |

<0.001* |

|

ΔLV ESV |

0.513 |

<0.001* |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

ΔStroke volume |

-0.384 |

<0.001* |

-0.319 |

0.011* |

-0.304 |

0.022* |

|

ΔCardiac output |

-0.337 |

0.001* |

-0.301 |

0.034* |

0.311 |

0.024* |

|

ΔCardiac index |

-0.314 |

0.015* |

-0.306 |

0.031* |

0.300 |

0.039* |

|

*p< 0.05 is statistically significant. Δ, change of LV function, abbreviations – see Tables 1 and 2 |

||||||

|

Table 4. Parameters associated with adverse remodeling |

|||

|

Variables |

Reverse Remodeling |

Adverse Remodeling |

p |

|

n=89 |

n=42 |

||

|

Demographic findings |

|

||

|

Age, years |

53.3(7.9) |

54.9(9.9) |

0.301 |

|

Gender, n(%) Female Male |

11(12.4) 78(87.6) |

7(16.7) 35(83.3) |

0.588 |

|

Age, years |

53.3(7.9) |

54.9(9.9) |

0.301 |

|

BMI, kg/m2 |

28.1(7.3) |

25.6(7.7) |

0.073 |

|

Hypertension, n(%) |

29(32.6) |

13(31.0) |

0.999 |

|

Diabetes mellitus, n(%) |

28(31.5) |

16(38.1) |

0.553 |

|

Hyperlipidemia, n(%) |

37(41.6) |

21(50.0) |

0.451 |

|

Current or former smoking, n(%) |

58(65.2) |

26(61.9) |

0.845 |

|

Systolic blood pressure, mmHg |

121(20.2) |

127.3(18.7) |

0.137 |

|

Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg |

74.3(13) |

78.3(13.8) |

0.165 |

|

Door-to-balloon time, min |

46.1(11.8) |

47.2(12.6) |

0.627 |

|

Symptom-to-balloon time, min |

343.5(86.2) |

340.4(82.5) |

0.846 |

|

Laboratory findings |

|

||

|

cTnT, ng/ml |

0.4(0.3-29.0) |

15(0.3-30.0) |

<0.001* |

|

CK-MB, U/L |

35(26-496) |

54(26-312) |

0.629 |

|

cTnT/CK-MB ratio, % |

1(0.1-49.0) |

16(1.0-89.0) |

<0.001* |

|

Hemoglobin, g/dL |

14.1(1.6) |

14.3(1.8) |

0.711 |

|

Platelet, x103 µL |

238(65.3) |

237.9(58.7) |

0.994 |

|

LDL, mg/dL |

140.5(39.4) |

126.7(42.2) |

0.252 |

|

HDL, mg/dL |

38.9(9.0) |

38.7(7.1) |

0.918 |

|

Creatinine, mg/dL |

1.0(0.2) |

1.1(0.2) |

0.133 |

|

Albumin, g/dL |

4.4(1.9) |

3.9(0.4) |

0.555 |

|

hs-CRP, µg/L |

19.0(1.0-139.0) |

10(1.0-28.6) |

0.224 |

|

Numerical variables are shown as the mean ( standard deviation or median (min–max). Categorical variables are shown as numbers (%). *p< 0.05 is statistically significant, abbreviations – see Tables 1 and 2 |

|||

According to this; It was determined that a 1% increase in the cTnT/CK-MB ratio increased ΔLV EDV by 0.5 fold, ΔLV EDV - 1.12 fold and the probability of adverse remodeling by 1.13 fold. A cTnT/CK-MB ratio >3.1 was able to predict adverse remodeling with 85.7% sensitivity and 74.2% specificity (AUC= 0.856, 95% CI= 0.788-0.924, NPV= 91.7%, PPV= 61.0%, p<0.001). The diagnostic performance of the cTnT/CK-MB ratio was superior to those of cTnT and CK-MB (Fig. 1C).

|

Table 5. Independent predictors of change of left ventricular volume and adverse remodeling |

|||

|

Variables |

Multivariable Regression |

||

|

β(SE) |

95% CI lower-upper |

p |

|

|

ΔLV EDV |

|

|

|

|

cTnT/CK-MB ratio |

0.55(0.08) |

0.38-0.72 |

<0.001* |

|

|

Adjusted R2=0.262; p<0.001* |

||

|

ΔLV ESV |

|

|

|

|

cTnT/CK-MB ratio |

1.12(0.28) |

0.54-1,69 |

<0.001* |

|

LDL |

0.09(0.05) |

0.01-0.19 |

0.043* |

|

|

Adjusted R2=0.277; p<0.001* |

||

|

|

OR |

95% CI lower-upper |

p |

|

Adverse Remodeling |

|

|

|

|

cTnT/CK-MB ratio |

1.13 |

1.08-1.20 |

<0.001* |

|

|

Nagelkerke R2=0.412; p<0.001* |

||

|

Effects of traditional risk factors were adjusted in all of the regression models. * P < 0.05 is statistically significant. β, regression coefficient; SE, standard error; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio, other abbreviations – see Tables 1 and 2 |

|||

Figure 1. Relationship of the cTnT/CK-MB ratio with left ventricular function and diagnostic performance in adverse remodeling

Discussion

In this study, the diagnostic performance of the cardiac enzyme levels at the time of STEMI in predicting the LV remodeling was investigated. The cTnT/CK-MB ratio, which is the ratio of two common cardiac biomarkers, was a strong predictor of LV remodeling. This relationship was independent of the traditional risk factors. Moreover, the cTnT/CK-MB ratio had a higher sensitivity and negative predictive value in predicting adverse remodeling. This is the first study to evaluate the diagnostic performance of the cTnT/CK-MB ratio in predicting post-AMI cardiac function and adverse remodeling.

In clinical practice, LV remodeling is often estimated based on enzymatic infarct size. The LV volume, which is strongly correlated with the post-AMI infarct size, is known to be affected by reverse remodeling (2, 20, 21). If the LV volume increases following AMI, the LV EF decreases (8). Therefore, ventricular remodeling is often evaluated based on changes in LV volume after AMI. However, it is clear that simple, cost-effective, easy, and accessible laboratory markers are needed to identify patients at risk of post-AMI ventricular remodeling. In this study, the prognostic value of the ratio of cTnT and CK-MB cardiac enzymes were examined, both of which individually showed high sensitivity and specificity in determining myocardial cell damage (22).

Previous studies have shown that peak cTnT, peak CK, and peak CK-MB after AMI are associated with infarct size, ventricular remodeling, and heart failure (23-26). CMR studies in STEMI patients have reported that cTnT was an independent predictor of the LV-EDV and LV-ESV indices (10), and predicted adverse remodeling (26). On the other hand, CK-MB often became insignificant in multivariate regression models (11, 26). In this study, peak (12-h) cTnT and CK-MB levels were positively correlated with the post-AMI ΔLV-EDV and ΔLV-ESV, and negatively correlated with ΔLV-EF. Moreover, the cTnT/CK-MB ratio was an independent predictor of the LV volume. These findings supported the fact that cardiac markers that reflect myocardial cell damage may also represent post-AMI heart failure. Our analysis demonstrated that the diagnostic accuracy of the cTnT/CK-MB ratio in predicting LV remodelling is more sensitive and specific than that of traditional cTnT and CK-MB alone. So, our findings may have important implications about the prognostic value of cTnT and CK-MB in clinical assessment.

The literature reported that a cut-off cTnT value of 3.26 µg/L can predict improved myocardial function with 80.9% sensitivity and 72.1% specificity (26). The findings herein regarding the performance of cTnT levels in predicting adverse remodeling were consistent with those presented in the literature. However, it was found that the cTnT/CK-MB ratio was superior to cTnT in predicting adverse remodeling in terms of the sensitivity and negative predictive value.

Study limitations

The major limitation of this study is that we did not calculate the infarct size and myocardial edema, which may have affected the relationship between the wall thickness and infarct size. Secondly, the definition of acute chest pain, which is necessary to determine the peak of cardiac markers (i.e., at 12 h), varied depending on the perception of the patients. Additionally, this study is exploratory and should be interpreted as hypothesis-generating analysis. There is need for larger studies which powered for clinical outcome.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the cTnT/CK-MB ratio >3.1 had a higher sensitivity and negative predictive value when compared to its components in predicting changes in the LV functions after STEMI, independently of the traditional risk factors. The diagnostic performance of the cTnT/CK-MB ratio may be superior to those of cTnT and CK-MB alone. The cTnT/CK-MB ratio can be used in clinical practice for risk stratification and treatment optimization.

Peer-review: External and internal

Conflict of interest: None to declare

Authorship: F. E., E.K., E.K., C.S., M.S.A., O.Y., A.K., G.K., M.A. F., C.O. are equally contributed to preparation of manuscript and fulfilled authorship criteria

Acknowledgement and funding: None to declare

References

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Kunst building, early 20th century, Vladivostok, Russia. Alexander Lyakhov, Vladivostok, Russia.

Copyright

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

AUTHOR'S CORNER